Breaking the Status Quo: How it Came to This

By Brent Toderash

Published Post Date

≅4,611 Words on Post Terms

Abstract

In this article, I highlight a few points of WordPress history that were early indicators of an eventual crisis in the project leadership. With increasing calls and support for a leadership change in the project, I review how the direction and goals set by Matt Mullenweg are increasingly at odds with FLOSS values and with the needs of the WordPress community. Matt’s needs are primarily aligned with Automattic’s over those of the community, and the strain is starting to show along numerous fault lines.

Looking for the TL;DR? Just skip to the “And Here We Are” Part.

Note: Things move too fast for long-form writers — as I was proofreading to hit “publish”, Matt posted a swipe at Heather Brunner and WP Engine on Twit-X and linked to an announcement cutting Automattic’s contributions to WordPress. While I don’t refer to that in this article, count it as another “final straw” for someone. This is the “here” we’ve reached: a kind of stalemate over who’s willing to contribute to the future of WordPress.

Context

The most recent watershed moment for WordPress came on December 20th, 2024, when Matt Mullenweg called a “Holiday Break” and shut down most services on the .org site, saying,

I hope to find the time, energy, and money to reopen all of this sometime in the new year. Right now much of the time I would spend making WordPress better is being taken up defending against WP Engine’s legal attacks.

This was quickly reported by Computer World as “WordPress.org statement threatens possible shutdown for all of 2025”, reflecting how community discussion picked up on the indefinite length of the shutdown.1 After a two-week shutdown, services were restored on January 3, 2025. The shutdown notice itself was like an impromptu edict — unplanned, undefined, poorly executed, and issued spur-of-the-moment, unilaterally. This has increasingly been the nature of Mullenweg’s actions over the past three months, and it’s a danger sign.

Breaking the Status Quo

In rapid response to Matt’s shutdown notice, Joost de Valk posted “Breaking the Status Quo,” causing immediate waves to break throughout the community and in online news sources2 A groundswell of support for Joost’s post came in the comments on the post, in Post Status Slack channels, and on X/Twitter by well-known contributors and community members, including Andy Fragen, Courtney Robertson, Tonya Mork, Scott Kingsley Clark, Luc Princen, Colin Stewart, Brian Gardiner, WP Engine, and others.3 Joost’s post called for a change in project leadership:

Our BDFL is no longer Benevolent, and because of that, speaking up in public is a risk. In an interview with Inc (which to be fair Matt called a “hit piece” himself) Matt said he preferred the term “enlightened leader” over “dictator”.

As Joost observed, “it’s fair to say that most in the community would disagree” that Matt displays the qualities of an “enlightened leader”.4 Joost doesn’t mince words, saying bluntly, “I think it’s time to let go of the cult and change project leadership.”5 He also calls for “Federated and Independent Repositories, in short: FAIR.”6

At the same time, Crowd Favorite CEO Karim Marucchi posted his support for Joost’s proposal.7 Karim affirms that WordPress is at a crossroads and writes about building upon foundational open-source principles to avoid “what befell other open-source projects that shrank or died while protecting one party’s market position.”8 His proposed roadmap spans project direction as well as technical and governance concerns.

Mullenweg Responds (Sort of)

In the comments on Joost’s post, Matt’s responded,

I think this is a great idea for you to lead and do under a name other than WordPress. There’s really no way to accomplish everything you want without starting with a fresh slate from a trademark, branding, and people point of view.

It was predictable, but at least an offer of participation was made. It’s clear Matt is choosing to withhold the support of his team and use of the WordPress mark, effectively saying, “No. Go ahead and fork it.”9 On Christmas Eve, he posted on Reddit,

I’m very open to suggestions. Should we stop naming releases after jazz musicians and name them after Drake lyrics? Eliminate all dashboard notices? Take over any plugins into core? Change from blue to purple?

I think we can brainstorm together and come up with way better things than I could on my own. ☺️ Also, Merry Christmas! 🎄

Matt: I’m very open to suggestions.

Narrator: He was not, in fact, open to suggestions.

While obviously intended to be tongue-in-cheek, it provides an indication of how seriously he takes the call for change. It’s likely these examples are characteristic of the extent and tone of the change he would be willing to consider, and once again illustrate how poorly he’s “reading the room.” Responses are pretty much as we’ve come to expect.

WordPress Without Matt?

Hendrik Luehrsen wrote, “The future of WordPress is… something we create together”, but Matt rejects this kind of future. Responding to the flurry of posts on the 20th and affirming Joost’s and Karim’s vision, Hendrik nevertheless wrote in a followup about a symbiotic relationship10 between Matt/Automattic and the community, where the community drives innovation and growth, and “Automattic’s resources, infrastructure, and stewardship provide[ing] a backbone that cannot easily be replaced.” In his view, the ecosystem depends on both “the leadership and vision provided by Matt and Automattic on one side, and the collective power of the community on the other.” In short, he doesn’t see a bright future for WordPress if it doesn’t include Matt.11

Matt is WordPress

Brian May (Retweeted by Matt)

Brian May recently posted his “strong opinion loosely held”, that “Matt is WordPress“,12 so he’s opposed to changing the governance structure. Matt seems to also believe that he is WordPress, retweeting Brian’s article and apparently using this concept as part of his legal strategy against the WP Engine suit.13 The majority of concerns Brian raises are specifically addressed by a proper governance model, and are better addressed by change than by status quo. I don’t dislike the BDFL model, but when it’s successful, it’s supported by a governance structure that WordPress does not have — and that’s the issue. WordPress may not have a bus factor of 1, but the lack of a governance structure around our current BDFL is an unacceptable risk for the community, both as a whole and in its individual parts. The fact that Matt is portraying himself as WordPress means he cannot and will not submit to any manner of governance reform.

There are times when disruption is both necessary and preferable.

The community is not united on this. Some can’t speak out, others are either content with Matt’s leadership or fear greater turmoil from a change than from the status quo. Perhaps it’s the “devil you know” argument. Up until September 2024, I had remained generally supportive of Matt’s technical direction despite concerns about his tenuous hold on an open source ethic and a number of governance and – let’s euphemistically say “public relations” – matters. My position changed in the weeks that followed WCUS 2024. Yes, it will be disruptive, but there are times when the disruption is both necessary and preferable. I believe the greater majority of the community is ready to and will support a change in governance, even if it requires some radical action. Everyone has their own breaking point, but I’d like to offer what I see as the trajectory that got us here.

The Road Behind Us

There are some key points from the history of WordPress14 that prove instructive leading up to Gutenberg being merged from feature plugin into core:

- 2009-14: Dual Licensing Controversy (Thesis, Envato/Theme Forrest)

- 2014 (January) Matt Mullenweg becomes CEO of Automattic

- 2014 (September): Five for the Future announced

- 2014 (September): Customizer introduced, version 4.0

- 2014 (State of the Word): Thesis controversy & domain purchase

- 2015 (December): Matt’s “Learn Javascript, Deeply” challenge

- 2016 (December): REST API moves from feature plugin to core, version 4.7

- 2016 (December): Launch of Calypso, new UI for .com powered by REST API

- 2016 (State of the Word): “WordPress Growth Council” to maintain market share

- 2017 (November): Customizer improvements, widget updates, version 4.9 (end of an era)

- 2017 (State of the Word): Gutenberg now 11 months in development; no default 2018 theme

- 2018 (December): Gutenberg included in core, version 5.0

With two major exceptions, three major WordPress releases per year has been the general pace of development for two decades.15 We’ve now had six years of Gutenberg releases, which fell short of the 2024 goal to ship the third of four phases. With two phases yet to complete, it looks like Gutenberg is set to become a decade-long project.16 The past six years have been tumultuous for WordPress, characterized not just by controversy but by increasing CMS market share and ongoing mergers and acquisitions in a space with a growing economy for the ecosystem and controversy over Matt’s leadership of the project, which have obviously taken a sharp uptick since September 2024.

Matt’s Ideals Have Gone to Seed

The reasoning behind “Five for the Future” was fundamentally flawed.

The answer to precisely when Matt’s ideals went to seed17 may vary for different people. For me, it was September of 2014. The impact of the flaw revealed then took ten years and twelve days to detonate. I believe the fact that so many people in the WordPress community learned about FLOSS from Matt meant they couldn’t see the misalignment here,18 but the reasoning behind “Five for the Future,” was fundamentally flawed, and was a primary indicator that Matt’s ideals had departed (or were never fully aligned with) open source ideals, or “the hacker ethic.”19 What began at WCUS 2024 is directly linked to its announcement. Contributing is a good goal, and there’s nothing wrong with a challenge, so I applaud those who have participated, but some may have felt the need to do so for the wrong reasons if they didn’t want to be accused of being an existential threat to the project.

We can make some further observations from the points of history I’ve listed.

Matt has had a string of leadership challenges, mostly self-triggered. This is the biggest one to date.

1. Matt’s Leadership. Over the past decade, we’ve also seen dissent mushroom within the WordPress community with challenges to Matt’s leadership,20 I disagreed with Matt’s handling of the dual-licensing debate, especially the fiasco over Thesis (.com).21 It turned out that spending $100k on a domain name and banning Envato from WordCamps was just foreshadowing how vindictive Matt can be.22

2. The Customizer. The UI direction from 4.0 through 4.9 (2014–2017) was the customizer, until Gutenberg was introduced. It’s been an incomplete artifact since then, leaving users hunting through admin settings pages as well as the Customizer to find what they need based on the whim of a developer deciding where to put a given setting.23 The Customizer is left with all the characteristics of an abandoned idea left to wilt in pursuit of something else that hasn’t been fully delivered yet, like a vestigial tail of the WordPress UI.

3. Calypso. Matt challenged the community to “learn javascript, deeply”, and a year later at the 2016 State of the Word, we had the REST API in Core and a demo of Calypso, a new admin interface built with javascript and the REST API. Calypso stood out to me at the time not just for the tech behind it, but because it was a major initiative developed for and launched on .com only. Automattic can certainly do this, but it felt like a procedural departure or change in philosophy.24 Whether it was or not, we might suggest that perhaps this is an indication that Automattic (.com) needed the UI upgrade more acutely than the rest of the community (.org) did.

4. Concern for Market Share. In the same SOTW 2016 presentation, Matt announced a “WordPress Growth Council” to help maintain market share, indicating that Matt was already thinking about preserving and increasing market share at a time when WordPress already commanded a very dominant position — 58.8% of the CMS market, or 25.6% of all sites.25 While market share is clearly a driving force for him, it’s generally a corporate concern and not a FLOSS ideal. Planning in this way can be viewed positively as being visionary, but this is more important to corporate market share than to FLOSS market share.26

Automattic needed Gutenberg more than by the community did, and controlled the project direction to largely allow Core to accumulate technical debt for two years before launching Gutenberg to a lukewarm reception.

5. Gutenberg. As of the 2017 State of the Word address, Gutenberg had been in development for 11 months and would take another year to merge into Core, with no major releases between. With groundwork laid by the REST API and Calypso proof-of-concept,27 Gutenberg now had almost all of the development focus. Seeing 5.0 at the end of 2018, a large part of the community resisted, feeling it wasn’t yet ready to be the default editor. Moreover, Gutenberg was needed by Automattic more than by the community, but with Automattic as the largest contribution sponsor, it controlled the project direction in support of Gutenberg. The upshot is that Core development had been effectively put on hold and allowed to accumulate further technical debt for two years in order to launch Gutenberg, to reception that was lukewarm at best.

Gutenberg was a Turning Point

What does all this tell us? Gutenberg has turned out to be a ten-year initiative, a major undertaking of its own that is bigger than the Core CMS it’s being bolted into. Core has had comparatively little attention for the past eight years.28 as Gutenberg chews up resources to the detriment of the rest of Core, with even the “official” performance team’s efforts remaining in an un-merged plugin. Despite Gutenberg dominating the project focus for 40% of its history, I’ll add one more to the litany of “WordPress is not” statements: WordPress is not Gutenberg.

WordPress is not Gutenberg.

Gutenberg was meant to be a turning point for WordPress, but in fewer ways than it was. Facing a loss of market share to SaaS solutions and the rise in popularity of page builders for WordPress suggested the need for a block editor in Core.29 At the outset, the community already had a variety of options in the page builder space — but none were in core. Production-ready or not, the intentional turning point was reached by adding a modern block-based browser. The unintentional turning point was Gutenberg’s mediocre reception, making it a target of criticism and the trigger for a fork of WordPress. I don’t blame Gutenberg, which I see as a symptom and not as the problem. By the time it was halfway through development toward merging it into core, the community was already starting to fracture under Matt’s leadership. The fissures were small — at first.

Understanding Why We’re Here

Matt’s Needs ≠ Community Needs

Every good work of software starts by scratching a developer’s personal itch.

Eric Raymond

Something I’ve been saying for a while (before this past September) is that Matt’s needs are no longer the same as the Community’s needs, if they ever were.30 Up until 2017 or so, they were aligned closely enough that everyone was being served by the project goals as they had been set for Automattic’s need to increase market share, as most of the product improvements that had been the focus also benefited the community. But here’s the thing: while open source project goals are largely focused on meeting a need, market share is a commercial concern. From a FLOSS perspective, the itch was scratched long ago,31 leaving market share as either a vanity or a revenue goal. There’s a tipping point for network value in a FLOSS project, which is reached when you have enough people in the community to maintain the software and support its users. This is an intrinsic measure (the need is met; the itch is gone), and not an extrinsic one, like market share (is anyone scratching more itches than I am?).32

Automattic has different needs from those of the WordPress Community because it largely has different competitors on a different scale.

Matt’s needs are Automattic’s needs rather than the Community’s needs;33 the gap has been widening, and don’t line up closely enough anymore. To explain, think about customers and competitors. In the CMS space, the Community members have either no competitors (they are end users of the software to directly or indirectly to compete in other markets), or their competitors are other agencies, developers, and freelancers. This sometimes means the second group competes with each other, but the primary objective for them is to offer an advantage over platforms recommended by competitors outside the community. This type of competition occurs on a site-by-site and project-by-project basis, and an army of community members have built WordPress’ network value in precisely this way.34 One-by-one addition builds market share, but it’s not a primary strategy for doing so at scale when looking at aggregate numbers is your benchmark. A primary strategy might be building a networked community of evangelists who go out and win users one by one.35

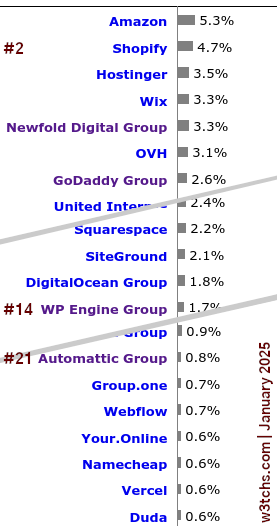

Matt has different competitors — or Automattic has, but they’re inseparable, and those interests come ahead of the community’s.36 Automattic’s competitors are Shopify, Wix, Squarespace, Webflow, Duda, Weebly, and GoDaddy, along with a basket of hosting companies offering a managed WordPress product, like WP Engine and a number of smaller ones in addition to PaaS companies like Vercel. Like Automattic itself, these are big players competing in bulk for market share, and Matt needs volume.

WordPress Market Share?

In a FLOSS project, the goal isn’t to establish a crushing market share that decimates competitors. Those kinds of monopolistic goals tend to be about money, power, or both.

In a FLOSS project, the goal isn’t to establish a crushing market share that decimates competitors. Those kinds of monopolistic goals tend to be about money, power, or both, while FLOSS projects rarely pursue even a dominant market share as a stated goal, unless that goal has some philosophical, moral, or ethical point behind it. An example might be to “democratize publishing,” or it might be that your software “protects the Internet from being overtaken by businesses or governments who may not have the world’s interests at heart.”37 or maybe you’re just doing your part to help ensure a largely spam-free email experience. In the case of WordPress, I would say the goal of democratizing publishing was achieved long ago by the internet itself.38 Despite being the stated goal, it’s not used as a factor in decision making, which suggests it’s no longer the mission, if it ever was. A larger market share doesn’t actually serve that goal, nor does Gutenberg. So why is Matt so committed to Gutenberg, and so concerned about CMS market share that he’s smugly said things like “We grew a Drupal in market share last year” — and in more than one State of the Word address?

Market Share: The Other Numbers

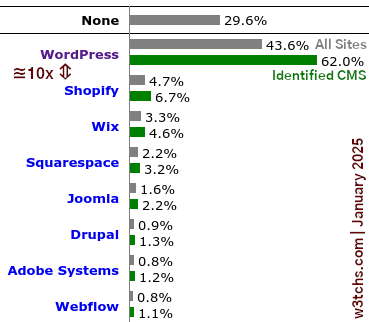

The first competitors on Matt’s list are made up of hosted CMSs. WordPress currently has 62% of the CMS market share.39 This is something of a triumph for WordPress, with almost 10x the market share of its next competitor. Matt’s problem is that the 62% isn’t his, it’s shared across the entire community and the ecosystem it supports. “Matt’s hobby site,” wordpress.org, touches all those sites, but his commercial site, wordpress.com holds just a fraction of them. Since the software is free, this shouldn’t matter – except when it does.

For the community, one of WordPress’ greatest strengths is avoiding vendor-lock to a CMS platform or host, and it’s those hosted CMSs that have to worry Matt. These are basically all growing, and when you hold as much of the market as WordPress does, pretty much anyone’s growth is going to come at your expense.Gutenberg was meant to address the biggest difference between WordPress and the hosted CMSs at the time: the editing experience. Back in 2014, wordpress.com was less flexible and offered fewer features than it does today40

But there’s another angle, with a very different story:41 Automattic only has 0.8% of the hosting market, well down from Shopify’s 4.7%, Wix’ 3.3%, Squarespace’s 2.2% and just barely ahead of Webflow (0.7%) and Duda (0.6%), none of which are as old as WordPress.42 This illustrates where Automattic is in a crowded market with a small share. Restricting the hosting offer to WordPress means offering a hosted CMS — like WP Engine or MPMU Dev or many others do. Matt can view the non-WP hosted CMSs as a threat to his hosting market share, which is a significant piece of Automattic’s recurring revenue.43 For Matt, the problem with WordPress is that he has to share its market — and the revenue — with others.

For this reason, what Matt needs and what the community needs are two different things.44

As a WordPress MU (Multisite) installation, the .com version of WordPress had less flexibility available to offer individual users.45 The limited flexibility of a decade ago was expanded, but they were already behind in the game, and the community may continue to see the .com product offering as a hobbled implementation that may not support what they want to do.46

So if you were Matt competing with Shopify for market share, what would you do? You’d probably buy WooCommerce (acquired in 2015). If you also had to overcome the perception that .com was hobbled and offered less than competitors who allowed installs of the .org version of WordPress, you’d work on expanding the flexibility you could offer in your hosting product. You might launch a VIP service (back in 2006) or increase what you could offer regular users, but you might also buy another brand to compete more directly with other managed WordPress hosts. Something like Pressable, for example (acquired in 2016). You might even create a PaaS offer, like wp.cloud. Bluehost moved onto wp.cloud infrastructure in 2024, so although it won’t be reflected in market share, Automattic is actually providing infrastructure to host 1.7% of the market — the same as WP Engine.47

WP Engine is something of an outlier. With half the history of Automattic, they’ve got twice the market share, offering the same thing: a hosted, managed instance of WordPress. When they were founded in 2010, WP Engine’s product offer would have been more robust than Automattic’s, at least outside of VIP (launched in 2006). Perhaps WP Engine executed a better marketing plan and crafted the better hosted WordPress product offering instead of the stripped-down .com version.48 By migrating Bluehost onto its infrastructure, Automattic’s capacity would appear to be similar to WP Engine’s. They’re effectively providing infrastructure for a similar number of sites, but Automattic’s revenue from the operation will be a fraction of WP Engine’s. WP Engine has points of presence in 14 of Google’s datacenters, while Automattic maintains a presence in 27 datacenters globally. This isn’t a measure of capacity, but Automattic likely has some excess to fill.49

And Here We Are.

Leadership of a FLOSS project must be more concerned with community than with shareholders, and for this reason, it takes a different kind of leadership.

Most conclusions about how it’s come to this point will be simplistic. Obviously there are many factors with different weighting and impact that combine in a complex manner, but the task is to somehow make sense of the way they’ve combined to produce the result we have, sorting out symptoms from causes. What I’ve outlined is an attempt to do this, and while not comprehensive, I believe there’s enough of a thread to explain it. The presenting factors over the past 10-12 years can help explain how and why WordPress has lost its way. At the same time, Automattic has likely not lost its way, as Matt’s leadership there seems to look after its corporate interests quite well.50 Leadership of a FLOSS project must be more concerned with community than with shareholders, and for this reason, it takes a different kind of leadership that I don’t believe Matt has been able to effectively provide for some time now.

Abuse of Power & Public Controversies

Going back 15 years or more, we’ve seen a number of instances where Matt has abused the power he holds over the project and the platform it gives him to speak. Going back to Envato and Thesis, we see the same kind of vindictiveness and retributive behaviour as we’ve now seen with WP Engine. It’s only gotten worse, with a clown emoji being enough reason to block or ban people — no matter who they are. Controversial statements tend to become PR fiascos as Matt rarely backs down from them. He’s said “once every five years or so” isn’t bad for these sorts of controversies, but the fact is that he starts them and escalates them with questionable actions — and, it seems, increasing frequency.

FLOSS Ideals versus Matt’s Ideals

While Matt openly and strongly supports the GPL, many of the other ideas he holds are inconsistent with long-established open source principles, particularly where economics are concerned.

Matt’s ideals do not fully align with historical forms of the hacker ethic and FLOSS ethos. While he openly and strongly supports the GPL, many of the other ideas he holds are inconsistent with long-established open source principles, particularly where economics are concerned.. This is seen clearly in his use of the free rider problem as a basis for “Five for the Future” and his use of “The Tragedy of the Commons” to support his actions in attempting to force WP Engine to contribute, casually dismissing sound evidence against it.

WordPress Mission

With the democratization of publishing not needing assistance, the stated mission of the project is questionable, and is not considered in any decision-making processes in the way that most organizations would ask how a new initiative serves their mission. Since the stated mission provides no direction, other goals and objectives, mostly unstated, tend to drive the project.51

Matt’s Concern for Market Share

With market share celebrated as a marker of project success, direction is set with this as a goal. As market share is a corporate KPI, the open source project objectives and direction are significantly impacted by the needs of Automattic as its major contribution sponsor.

Gutenberg’s Failure to Deliver

Gutenberg shows the hallmarks of a failed software project.

Gutenberg doesn’t have to be labeled a bad idea or a poor product for it’s main flaws and unintended impact to be acknowledged. Having failed to meet its objectives in a timely manner and under-delivering on its expected ease of use, Gutenberg shows the hallmarks of a failed software project. WordPress core accumulated technical debt while development efforts focused on Gutenberg, and has not made a plan to address it.

Matt’s Leadership

Lacking the formal structures necessary for a successful BDFL (or any) model of open source project governance, the project faces significant risk of non-benevolent actions by its leader. With increasing public criticism from the community, Matt’s actions have become increasingly more chaotic since September 2024. A number of appeals for governance reform have been made, with a lack of any receptivity on Matt’s part.52

The Bottom Line

Matt has a fiduciary duty to Automattic’s shareholders, but with no formal governance structure in place for the open source project, he has no such duty toward it.

It isn’t not about the bottom line. The common thread is that Matt’s decisions about the project direction are more heavily influenced by Automattic’s needs than by the community’s needs. Although he has a fiduciary duty to Automattic’s shareholders, with no formal governance structure in place toward the open source project, Matt has no such duty. As the needs of each became increasingly less aligned, the fault lines began to show, with increasing stressors on the relationship between Matt and the wider community. Given Matt’s behaviour has become increasingly less predictable, the community faces the increased risk of being cut off from the project into which they’ve poured countless.volunteer hours — and some have already been locked out.

There’s naturally a lot of talk about what to to next, and everything’s about to come down to governance.

Where do You Share?

Where do You Share?

Notes

[footnotes_block]Related Posts

- Why Unmasking The Tragedy of the Commons Matters

- Breaking the Status Quo: A New Roadmap

- Breaking the Status Quo: How it Came to this (This Post)

Notes

- Rae Morey called it “unexpected”. Matt Mullenweg Announces Unexpected Holiday Break for WordPress.org Services, Rae Morey, The Repository, December 20, 2024. Her article states, “It’s the first time in WordPress.org’s 21-year history that it has shut down for the holidays, and it’s unclear when the services will resume.” Mullenweg-owned WPTavern’s coverage was simply a link to the announcement without commentary. Search Engine Journal‘s headline reported “Mullenweg’s WordPress Pause Triggers Unexpected Complications” and described some of the fallout it created. As SEJ’s Roger Montti wrote, this was a tipping point for Joost de Valk.

- e.g., The Repository: Joost de Valk Calls for End to Matt Mullenweg’s BDFL Leadership of WordPress; WP Tavern: Joost de Valk Calls for Breaking the WordPress Status Quo, Community Reacts; Search Engine Journal: Yoast Co-Founder Calls For WordPress Leadership Change – Mullenweg Resists.

- Only naming those who have spoken publicly, for well-established reasons.

- The day before, Inc. had posted an interview with Matt, Is Matt Mullenweg the Mad King of WordPress? (Doug Freedman, Inc., December 19, 2024), based on an interview from late October. Matt responded, calling it a “hit piece.” In discussing those pieces on Post Status Slack, I pointed out that “‘enlightened leader’ is more arrogant than ‘BDFL’, so not an improvement.” It would be fair to say that Matt’s track record includes a lot of things generally not considered benevolent or enlightened. This is far from the first time the benevolence of Matt’s BDFL-ship has been questioned in the past few months (or before), with the sentiment being echoed repeatedly in public and private online discussions.

- Joost outlines five things he’d ideally like to see, which I summarize: (1) Establish a foundation with a diverse board of industry representatives; (2) transfer wordpress.org and other community assets registered to Matt to the foundation; (3) give the trademark to the public domain or establish a to freely allow its use; (4) open foundation sponsorship to companies and individuals, with perks given transparently; and (5) create a governance structure with a number of small teams responsible for different aspects of the project and community.

- Disclosure: I’ve been involved with AspirePress in working toward this goal, and a number of other efforts exist (some prominent, some not) who may currently appear to have made more progress based on public statements. At the time of this writing, AspirePress has reached its “MVP” stage and is privately doing alpha/beta testing while continuing work to build out features. Building a federated, distributed software repository is a technical challenge when the goal is to prevent any one person or organization from controlling it. Achieving the goal extends well beyond shipping code, and three things differ from the other published efforts in the approach by AspirePress: (1) AspirePress has filed paperwork to establish a nonprofit company on the way to 501(c) status, and has a draft governance model; (2) AspirePress is standing up infrastructure as well as software, including sponsored CDN from Fastly; and (3) instead of being driven by an individual, AspirePress is a community effort with well over 100 members active in its Slack channels and multiple contributors on Github; the community has done more than a dozen translations of the plugin so far. The group would be pleased to work with any and all who share the objective, but most of the alternative efforts have chosen to “go it alone” for reasons which are mostly not shared.

- Karim Marucchi, “Breaking the Status Quo: A Vision For a New WordPress Business Roadmap”. His and Joost’s posts link to one another, and while not explicitly stated, they appear coordinated, referring to prior conversations between the two authors. As background for anyone unfamiliar with this part of the history, Crowd Favorite was one of the first WordPress-focused agencies, founded by the late Alex King. Alex was a “community giant,” an original WordPress contributor whose stature within the community cannot be overstated. He passed away from cancer in September 2015.

- He offers five priorities, summarized as (1) securing and modernizing the supply chain with a federated repository; (2) defining and creating “the commons” with proper governance; (3) creating a roadmap for the “Open-Web’s Operating System” to modernize the tech stack at every level; (4) open source as an innovation hub for creating a pliable, customizable, and modular core; and (5) leading improvements in accessibility and in the management of privacy and data ownership.

- Matt is obviously unreceptive to any of Joost’s five points. We can infer that “people” refers to the paid contributors he directs, as he cannot control or speak for volunteers, for contributors sponsored by third parties, or for the wider community of users and stakeholders, including agencies, web hosts, plugin developers, or theme shops. In Matt’s view, Joost’s proposal must be an offshoot of WordPress and its community, without his support. He has often said publicly that anyone is welcome to fork the code at any time under the GPL, and it seems he views this effort toward governance reform in the same light. I’ve always seen Matt’s invitation to fork as akin to bluff-calling: he knows it’s not that simple, and citing freedom to do so makes light of it.

- Hendrik Luehrsen, Symbiosis, Not Stalemate: Bridging the Gaps in WordPress Governance, December 21, 2024. He acknowledges that the relationship has come under significant strain. His earlier roadmap piece was “WordPress isn’t WordPress anymore“, December 10, 2024

- I’ll disagree partially here. Matt has tended to block innovation from the community unless it happens independently, outside of Core (and sometimes even then) as he uses his BDFL power for gatekeeping. Automattic is a big factor in supporting the community, but “not easily replaced” is not irreplaceable, and I think In the current climate, while not being simple, it will prove easier than may be feared. I think we can safely say that the relationship betwee Matt and the community has gone from symbiotic to toxic, already with some people seeing as parasitic in the way volunteer labour has been used to build up Matt’s personal website, wordpress.org.

- Brian May, “Matt is WordPress“, December 27, 2024. I love the “strong opinion loosely held” phrase as well, recommend his post even if you disagree with its title or premise, as he provides a nice overview while raising some good questions that deserve thought, and eventually, a more detailed answer than what I’m giving them here. He affirms the BDFL model of a visionary leader, cites other open source projects, and outlines a specific set of concerns. I think for each of the open source projects he cites, there’s likely an equal and opposite example found in a broader survey.

- Mike Dunford, in a Twitch stream on January 2, 2025 (Archived on YouTube), said “In fact – so basically the more Matt makes ‘WordPress c’est moi‘ the theory of the case, I think the more trouble he’s going to get into. And he is very much making ‘WordPress c’est moi‘ the theory of his case.” (at 0:45:00) He continues, “The more Matt makes ‘WordPress c’est moi‘ the theory of the case, the less stable he makes WordPress as a thing anybody should be using.” He then observes (at 0:47:00) that Matt’s argument is becoming intensely that he is WordPress, and goes on to speculate that at some point it will be determined that his case is stronger if the use of his powers is not singly focused on WP Engine, but applied to others as well.

- For background, I was a b2 user before WordPress, so I’ve been around for the long ride. This means I remember the aftermath of Six Apart’s license and fee changes for Movable Type in May of 2004 that sparked significant growth for WordPress starting with version 1.2. I recall being excited to install the update (1.5, “Strayhorn”) where “Pages” were introduced and would resolve a problem I had, followed by rich text editing in 2.0 (though I still tended to write raw html for a long time out of habit). I remember the MU code merge in 3.0, which landed in the middle of a project where I’d enlisted Aaron Campbell to help build a SaaS app using Multisite as a framework. Then there was the Customizer in 4.0, Gutenberg at 5.0, and many others along the way. The technical side was good for many years, though I of course I also remember controversies in the non-technical end of the pool.

- Three releases per year, with more regularity since 5.0. From 1.0 through 4.9, the same was generally true, with 2-3 releases per year on a less regular schedule. The first major exception was from 2.9 to 3.0, with a 6-month interval before the “code merge” was shipped, and 8 months after it, until the release of Post Formats in 3.1. The most significant exception is a year-long gap before 5.0, when Gutenberg was shipped in December 2018. There was also no new default theme for 2018 in order to focus on the block editor.

- Not to say this is inherently bad; sometimes a good plan needs a very long view, but that was not the expectation here. Gutenberg is still undergoing UI changes and updating things that should have been polished by now, and as a project undertaken largely to retain market share, it’s taken far too long to deliver the basics following the two years working toward an initial release that clearly caused delays in releasing updates to the rest of Core. Gutenberg also seems to have some misplaced priorities. Duotone filters and support for epub may be cool and all, but nobody is clamoring for either one, illustrating misdirected effort in view of Gutenberg’s usability issues and WordPress’ decaying core. In this situation, it does not strike me as wise to embark on collaborative editing (phase 3) when Gutenberg has been shown to be hard enough to use on your own. The harsh reality is that an objective review of Gutenberg would be hard-pressed not to call it a failed project. This doesn’t mean it was ill-conceived or a bad idea, just that the project has failed in its execution.

- For those unfamiliar with the idiom in English, going to seed comes from horticulture and refers to the phase where flowers have ceased blooming: it’d be one step past another idiom, “the bloom is off the rose.” In its wider metaphorical use, it means something is in decline, having lost its earlier appeal or value.

- This is the reason I began writing on this site, to provide a corrective to some FLOSS concepts that parts of the community may not well understand.

- Five for the Future was a challenge Matt issued in September 2014, but which lacked “official definitions” until 2022. I’m not the only one who saw issues with it and had concerns at the outset. See for example, Ben Metcalfe, “The feasibility and governance concerns behind 5% contribution to WordPress Core“, October 2014. Making it concrete and trackable was the beginning of the end, and others saw issues at the time as well. See for example Cameron Jones, “Why I’m Not Sold On ‘Five For The Future’“, August 2022. Either most people were okay with the program or just tiptoed around it hoping it wouldn’t become the problem it has.

- Here I’m thinking in part about Matt’s history of making what appear to be rash statements (e.g., “existential threat” claims and other PR disasters) that raise controversy over his handling of them, as well as incidents where he’s been seen to have violated the Code of Conduct or been complicit when others have done so. I’m mentioning but not delving into those here, partly because I’m not familiar enough with the details to avoid misrepresent them, and partly because dredging up details can do another form of harm to those involved. I’ll just say there were a lot of things leading up to “car full of hammers.”

- I stayed out of it generally because I agreed with Matt — while permissible “under the letter” of it, dial licensing is against the spirit of the GPL.

- Bringing it up in his “State of the Word” for 2014 was also not a good look, and revealed something else about Matt’s character: beyond being vindictive, he tends to be smug when gloating. PR Tip: There are no contexts where bringing up Thesis makes Matt look good, but he did it again anyway in a non sequitur during the previously mentioned interview with Inc.

- Often these settings are still found in more than one place (menus, general settings) but plugin authors may extend the settings in only one of those places. Within Gutenberg, you may have a defined colour palette that isn’t available in the Customizer, and you might (or might not) be able to center the same text in more than one spot on the same screen.

- At the time I recalled Matt having said he would open-source anything except payroll, so it struck me as somewhat off that this wasn’t a community or .org initiative with a canonical feature plugin; it was something for .com-first, despite being demonstrated to the wider (.org) community. Parts of what we saw then (at least its look and feel) are starting to appear in WordPress Core now, eight years later.

- The council took a bit of time to get rolling and is not very high-profile currently, but since then, Matt has thrown out goal numbers like 50% and 85% as not being unreasonable market share goals.

- Not that it’s unimportant due to the need for network value, but it’s important in a different way and to a different degree.

- If you include those as part of the Gutenberg timeline, it adds another year to all the numbers.

- Of course there have been a number of additions and improvements, but a lot of these are to support Gutenberg or serve a specific niche for developers rather than to modernize or extend Core.

- With the majority of the existing block editor plugins being (in my opinion) not well-written or well-architected but growing rapidly as they enabled easier design by non-developers, this seemed logical, but at the time, those existing third-party solutions were largely meeting the need, and as Joost pointed out, Elementor was doing it well enough to preserve WordPress’ market share. It’s not entirely clear why Gutenberg was started from scratch rather than adopting or acquiring something like Elementor either as a feature plugin or merging it into Core. The most obvious explanation would be that Matt wanted an entirely different tech stack for the block editor, despite how well Elementor was already leveraging the Customizer and the existing UI at that time, while the cynical answer would be that he simply wanted it to be his own invention. Matt began with the charge to “learn javascript, deeply” and has been pushing Gutenberg development ever since.

- Feel free to substitute “wants” or “goals” here and elsewhere; the intended meaning or implications won’t change.

- Consider the stated mission: increasing market share is not a requirement to democratize publishing. Further, Matt’s “origin story” for WordPress describes an “itch” that he and Mike Little shared, which led to the founding of the project as a fork of b2.

- I’m going to say some things that sound like I think market share is irrelevant to WordPress, but that’s not what I’m saying. The numbers matter, but they should not be a motivator, and it will not be good for the marketplace for them to get significantly larger they are now. In his recent roadmap post, Joost de Valk made very good use of market share data; I see this as a helpful exercise in what we can learn from it to better serve the community, rather than simply how big we can grow it.

- I will interject here that I’m convinced by the alter ego argument that Matt (aka wordpress.org), Audrey Capital, Automattic, and the WordPress Foundation are indistinguishable from one another in any real or practical way. To illustrate, Audrey Capital – an investment company – hires a developer, who goes to work supervising and collaborating with staff of Automattic to write software, including work on Matt’s personal website. To meet operational needs of Matt’s personal site, Automattic hires staff and puts them to work on it. Automattic and Audrey both have outside investors, none of whom seem to complain about enriching the value of Matt’s personal website through company resources. For its part, the WordPress Foundation seems not to have staff directly either, so its labour must come from Automattic, Audrey, or outside volunteers many of whom built up the value of Matt’s personal website thinking they were volunteering for the Foundation. What I’m not convinced is that Matt is WordPress. He controls the brand, and to that extent, Matt is WordPress, but the more significant definitions of WordPress as a software project and as a community are not Matt, and while we have lacked some clarity of terms to this point, the differences are becoming glaring.

- There are still other parts of the community, like commercial plugins, theme shops, and web hosts that compete differently and based on size, may switch from one-by-one measures to bulk market share measures. These make up the “ecosystem” part of the community, which is also their target market to serve.

- Beware though: you have to nurture and inspire that community; take them for granted, offend them, disregard them, devalue or dismiss them, and you’ll lose them. In the immediate aftermath of WCUS 2024, I had said Matt would lose the community, and seeing how fast things turned, I quickly adjusted to say he had lost the community by the end of September 2024. His actions since then have not restored any faith, but driven them further away, eroding the size of the community who are siding with him on WP Engine and other matters.

- This reflects neither benevolence nor enlightenment.

- Internet Systems Consortium (ISC), About Us – ISC (Accessed December 2024); ISC is responsible for BIND.

- After the internet, social media likely democtratizes publishing more than WordPress ever has. Although it tends to be a great rallying cry and was an in vogue sentiment in the early 2000s, in my mind, it’s questionable to what extent it was ever a necessary goal for the project — I was publishing online back in 1999, and never really felt a lack of options for a publishing platform. This is why I began using b2, as the GPL (or compatible license) was already a pass/fail requirement for me, and I had a number of options even then. Further, there must also be a point where overachieving the goal causes the pendulum to swing the other way. If you start to approach monopolistic control of the market, you’ve actually un-democratized publishing.

- Followed (in order) by Shopify, Wix, Squarespace, Joomla, and Drupal. It makes no sense to be awake at night worrying that your 62% share will suddenly evaporate — when you take that much of it, you’re not at the crowded end of the market, which at this point of imbalance really needs stronger competition. The exception might be worrying that you’ve done something to cause its sudden evaporation.

- The goal for Gutenberg was to offer something as good or better than the hosted CMSs. Don’t forget wordpress.com is basically a hosted CMS, and ten years ago its users couldn’t install their own plugins or themes (commercial, private, or custom), so the best they could do was purchase one through .com or use the subset of plugins offered, which wasn’t the full repository. You might even have called it a “hacked-up, bastardized simulacra of WordPress”, unless you knew that the singular form of the word is “simulacrum”, or if you understood and accepted that anyone is free to offer services using the software with supported configurations which are not the defaults. Every managed WordPress host does this, including Automattic. If they aren’t managing the configuration, then they aren’t managing WordPress.

- Another disclosure: I’ve been in the hosting industry as co-owner of an ISP and later a pure hosting service for going on 25 years now. We began offering managed WordPress hosting in 2012; it stood out a lot more as a differentiator back then.

- The figure is for Automattic Group, which includes Pressable, WordPress VI,P and wp.cloud. Amazon is the largest at 5.3%, GoDaddy is at 2.6%, and WP Engine holds 1.7% (17.1% of which is Flywheel). Newfold Digital (formerly EIG, or Endurance International Group) is reported as 3.3% including several of its brands, though they own many more than those listed. I can’t escape the observation that despite Matt singing the praises of Newfold, EIG has had a very poor reputation within the hosting industry for a long time, which it earned by doing precisely what Matt accuses Silver Lake of doing with WP Engine. While I’m making observations, I’d so observe that although Matt has often used the term “private equity” as if it settles all arguments about nefarious intent (though sometimes with a caveat), Audrey Capital is essentially a Private Equity firm, like BlackRock or Silver Lake – it’s just much smaller and has a different focus on angel investments.

- Automattic is diversified in other ways through different non-WordPress holdings, and many sites that Automattic is not hosting still contribute recurring revenue through other products like JetPack, WooCommerce, and Akismet.

- Other web hosts have their own needs, which are more closely aligned with the community they serve than with Automattic, with whom they compete. For web hosts, the rest of the community is also its market, so what the community needs is largely what web hosts need. Other hosts seeing hosted CMSs as direct competitors may choose to offer managed WordPress hosting to make it easier for users (Pagely, WP Engine, and almost everyone else now), and want WordPress to do well for this reason. If they aren’t completely focused on WordPress, as few are, they may also offer their own hosted site building tool (GoDaddy and others).

- History lesson: despite a round of people calling for the removal of multisite as irrelevant a few years ago, suggesting it was an unnecessary feature added in version 3 essentially because they couldn’t imagine a use case (which there are many), the fact is that like WordPress and b2 Evolution, WordPress Multisite was forked directly from b2 by Donncha O Caoimh, and originally called b2++ (I installed and tested all three back in the day) before changing its name to WPMU (for multi-user), then WordPress Multisite. It largely maintained compatibility with WordPress plugins and themes, but prior to version 3.0, if a plugin or theme developer skipped a few steps, Multisite support might be dropped, either accidentally or intentionally. Donncha was Automattic’s first employee while Matt was still working at CNet, and the hosted version of WordPress (.com) was set up on what became WordPress Multisite. The two code bases were merged in version 3.0, which is referred to as “the code merge” by long-time community members. Multisite support in core wasn’t a new feature at all, it was a means of having to only maintain one code base rather than two, and for that reason, it won’t (nor should it be) removed, although imo the constant to allow it should be removed from the default wp-config.php file. Multisite should require a bit more configuration to set up – as it is now, it’s too easily enabled by people who don’t have the ability to maintain it. But I digress, again. Go check out a 2013 interview with Donncha.

- After all, many of its early users were bloggers wanting a free platform, including a large number who were fleeing from Movable Type. The product was necessarily stripped-down for a long time. WordPress VIP was added later to serve a very different clientele.

- wp.cloud also hosts sites for some .com plans; it was officially launched in 2021, but has been Pressable’s infrastructure platform since 2019. In the 2024 announcement, when Bluehost moved onto the platform, Automattic called them “one of the largest website hosts in the world”. In fact, they are owned by Newfold (EIG) and account for 27.4% of Newfold’s hosting share, which is 0.9% share among all hosts. On its own, it’s slightly larger than Automattic. With no details disclosed about the nature of Newfold’s license to use the WordPress trademark, we can surmise that this is the most likely mechanism for the consideration — perhaps it’s a “perk” based on the amount that Bluehost is already paying for the PaaS infrastructure, as it may be hard for them to talk about their platform without using the trademark in some fashion, and if they do, it’s actually to Automattic’s advantage.

- Despite what Matt called it, the software they offer is still WordPress in a managed form.

- And, if you were Matt and were looking at the market share and revenue numbers and the amount of work you’d put in, all this might stick in your craw. The reality is that not everyone is going to make the same amount of margin, even doing the same thing. This is where the private equity complaint comes in, since increasing margins and net profit is usually a specific focus. This has always been EIG’s (Newfold’s) model as well with the hosting brands they acquire. For both, maximizing profit can tend to lead to a decline in service. Matt is correct about the potential for this, and while it may not apply for Bluehost, it could still apply with other Newfold hosting brands.

- This is not intended to be a “hit piece”, just an attempt to deal with the reality that a leadership change is necessary.

- Lack of a clear mission appears to be part of the reason why Joost de Valk stepped down as “CMO” for WordPress in 2019.

- Rather than list individual ones at this stage, we can just take note of “WordPress Contributors and Community Leaders Call for Governance Reform in Rare Open Letter“, Rae Morey, The Repository, December 2024 and over 250 signatories at wpmustwin.org.

Pingback:Breaking the Status Quo is The Future of WordPress – YAWP.foo