Reframing the Maker-Taker Problem

Abstract

A number of theoretical models suggest that there’s a problem with sustaining development of open source projects. The Free Rider Problem and the Tragedy of the Commons are the leading two, but a more recent theory called the “Maker-Taker Problem” has been put forward by Drupal founder Dries Buytaert. His description of the problem has been generally well-received within the open source community. His theory is better-reasoned and takes into account some of the issues with other models. Unfortunately the theory still suffers from a few flaws that call its conclusions into question. In addition to one of its key foundation sources not reflecting the impact of online collaboration, some of its presuppositions mean it cannot be taken as a certainty, and make it potentially applicable to open source but not to free software. After describing the terminology, this article considers the Maker-Taker Problem as presented, highlighting certain weaknesses that make the model unreliable for defining and addressing the problem it presumes.

Prologue: Defining Our Terms

Free, Open, & Available

Open source and free software do not mean the same thing.

Before diving in, it’s worth pointing out (especially for those who came later to the movement) that Open source and free software do not mean the same thing. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a lot of debate between the two figures responsible for defining the terms, some of it a bit heated.

Since the 1980s, Richard Stallman had argued that “free software” was a moral imperative. From the late 1990s, Eric Raymond argued somewhat more pragmatically for an open development model based on technical merit rather than any ethical imperative.1 With the “free” in free software being ambiguous in English, “free as in speech” was used to distinguish from “free as in beer” — liberty versus cost-free. Eventually, the word libre began to be used to refer to freedom (as opposed to gratis). Alluding to this, Stallman’s biographer fittingly titled his book Free as in Freedom. Many today don’t realize there is a philosophical difference, or see it as a nuance that doesn’t hold much significance. Despite the fact that many of us tend to use the terms somewhat interchangeably with the acronyms OSS, FOSS, F/OSS, and FLOSS, there are times when it helps to highlight that difference even though the inclusion of both in a single acronym tends to obscure it. Fundamentally, the difference is in the “why”. In the Venn diagram of the two, the placement of the “why” can be extremely significant, and foundationally so.

Open source is a development methodology; free software is a social movement.

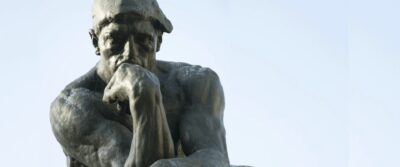

Richard Stallman

The FSF defines free software and maintains a list of compatible licenses, while the OSI created The Open Source Definition listing criteria for a license to appear on its list of certified licenses. The two lists look a lot the same, and others have attempted to explain the difference. Stallman describes them as “almost the same category of software, but they stand for views based on fundamentally different values. Open source is a development methodology; free software is a social movement.” The views are not incompatible and the list of licenses is almost the same, but the differences hold the key to understanding some of the reasons people may choose a license like the GPL.

A third type of “open” is under a “source-available” license. These licenses are not approved by the FSF or the OSI for one reason or another, but generally they put strict requirements upon the licensee’s ability to view or change the source code, and may not guarantee the ability to do either. Although they attempt to give the appearance of it, these license is not considered open source and of less concern to our present discussion.

Community Components

Another set of terms tends to be used with a general assumption that their meanings are understood. These terms have distinct meanings in the field of ecology, and while not leaning on those definitions here, the distinction should relate in both arenas. We talk about “the community,” and about “the ecosystem” — both collective nouns.2 When used synonymously, the terms are broad, and refer to the group of people using the software, including developers and contributors as well as end users and companies who provide related services to the community.

Community, Ecosystem, Contributing Members, & Users all represent similar and overlapping groups, but there are important distinctions between them.

Whether or not others use the terms interchangeably, I see them as overlapping but different things, and it can be helpful and necessary to differentiate between these terms and the sub-groups of which they are made. To begin, we can say that the ecosystem refers to a group that is commercially-focused. The community doesn’t necessarily exclude commercial interests, but this is not the focus. The ecosystem, on the other hand, always has an aspect of commerce to it.

Business interests serving the community are also part of the ecosystem, which I describe as the economy that the software and its community supports. In other words, the ecosystem is the economic engine that uses the software to generate revenue through commerce within the community, making it a narrower term. This is where we see revenue-generating models like commercial software support and paid software licensing for extensions to the free software, which may appear to be less altruistic than direct contributions to the core software itself, though this is often a false reading.

Community is a different kind of group, and includes different types of members. It may be helpful to think of one distinction within the community as contributing members and users.3

Not all users contribute directly to the ecosystem, and may not feel “connected” enough to consider themselves a part of the community, particularly if they make use of the software outside of its ecosystem.4 Those who purchase services from within the ecosystem become customers within it, contributing in that fashion. Users or community members who use the software to generate revenue for themselves or others are also part of its ecosystem, whether they provide support, training, consulting or add-on products. The same individual can be part of all of these, acting in one role or another at different times, so even if the groups were exactly the same, they are differentiated by the role they are expressing at different times.

The community is a primarily a group of contributors and promoters of the software. It overlaps significantly with the set of end users of the software. The ecosystem overlaps with both of these, and is differentiated by the presence of some form of commercial transaction. The ecosystem includes corporate interests who may only be tangentially involved with the software to one degree or another. For example, a tire manufacturer might be part of the ecosystem around a particular auto manufacturer — or several.

Brief Recap: Models & Theories

As we’ve shown, with a near-zero cost of production, free software is not subject to the free rider problem, instead benefiting from the network value they add. This is so because software is a non-rivalrous good, making it a different kind of commons than the traditional forms to which these economic models have been applied. Thanks to the network value of its users, free software becomes not only non-rivalrous, it becomes anti-rivalrous: the more users, the more network value. As Lawrence Lessig so aptly put it, “I am not only not harmed when you share an anti-rival good: I benefit.” We’ve learned that FOSS is also not subject to the discredited tragedy of the commons, because not only is it anti-rivalrous, Hardin’s predicted tragedy is not an inevitability.

Being anti-rivalrous, free software is not subject to the free rider problem, nor to Garrett Hardin’s tragedy of the commons, which does not suffer the inevitable outcome he predicted.

So what kind of problem does FOSS have? It’s clearly a widespread assumption that free software must suffer from some kind of economic problem in its funding model, and most attempts to address it by offsetting a perceived imbalance between users who contribute and users who do not. I briefly touched on the “Maker-Taker Problem” when discussing free riders, as it is somewhat related but features some specific distinctives to consider in more detail. This more recent economic model is described by Drupal project leader Dries Buytaert in a 2019 post, “Balancing Makers and Takers to scale and sustain Open Source”, where he offers some good insights, which came up again in the wake of Matt Mullenweg’s war on WP Engine.5. While I agree with much of what he’s said, we’ll see that it’s still not quite the right angle of approach.

The Maker-Taker Problem

Identifying Makers & Takers

The terms “maker” and “taker” sound more parasitic than symbiotic, but are described less pejoratively in Dries Buytaert’s explanation of the problem as he sees it.

My first issue with the “Maker-Taker” terminology is that like the free rider problem, the terms sound more parasitic than symbiotic. These are defined less pejoratively within the description of the problem, so it’s unfortunate that the presenting terms aren’t intended at face value.

Briefly defined, makers invest in maintaining open source software, including non-code contributions like documentation and event organization. Takers are companies “from technology startups to technology giants” that monetize the software without contributing to it.6 Recognizing that not all companies are able to contribute, Dries writes, “We limit the label of Takers to companies that have the means to give back, but choose not to.” He also points out that while “takers” has a negative connotation, he doesn’t think of it that way since there’s no malice in it, and observes that an organization can be both a taker and maker at the same time by being users of two different free software projects, but contributing to only one of them. He summarizes:

The difference between Makers and Takers is not always 100% clear, but as a rule of thumb, Makers directly invest in growing both their business and the Open Source project. Takers are solely focused on growing their business and let others take care of the Open Source project they rely on.

At this point, Dries makes a generalization we’ll need to watch for, saying that takers usually enter the ecosystem with a product offer similar to the makers’ offer(s), but without investing in the free software project. Assuming that the makers’ offer(s) were the funding model for the software, he suggests that by being able to focus on commercial growth without the cost of software maintenance, the taker has a competitive advantage. While this may be true, with a generalization and an assumption at play, we have to stipulate that it may not necessarily be so, particularly considering any advantage conveyed by the Maker’s closer association with the software.

An investment example is used to suggest that the taker can leverage the maker’s investment in the software and direct their own finances to innovate faster.7

Takers reap the benefits of the Makers’ Open Source contribution while simultaneously having a more aggressive monetization strategy. The Taker is likely to disrupt the Maker. On an equal playing field, the only way the Maker can defend itself is by investing more in its proprietary offering and less in the Open Source project. To survive, it has to behave like the Taker to the detriment of the larger Open Source community.

“Taker” Behaviour

Along with the free rider problem, Dries takes up other topics we’ve covered, such as the prisoners’ dilemma, “rational behaviour”, and how a taker’s behaviour can cause changes in the maker’s behaviour. He contends, “Takers harm Open Source projects. An aggressive Taker can induce Makers to behave in a more selfish manner and reduce or stop their contributions to Open Source altogether. Takers can turn Makers into Takers.” We considered this idea in the free rider problem, where the expectation (or fear) of how person A will act changes person B’s behaviour to match the actions they feared that person A would take, making the result self-fulfilling.

Dries Buytaert views free software as a public good, but suggests that free software projects are also common goods, with a rivalrous nature not for the software, but for the customer.

Dries views free software as a public good (non-excludable and non-rivalrous), but suggests that free software projects are also common goods, with a rivalrous nature not for the software, but for the customer, which we can understand as a subset of users within the ecosystem:

For end users, Open Source projects are public goods; the shared resource is the software. But for Open Source companies, Open Source projects are common goods; the shared resource is the (potential) customer.

In other words, “[W]hen an Open Source end user becomes a customer of Company A, that same end user is unlikely to become a customer of Company B.” Underscoring this distinction in the free rider problem, he cites network value as the reason that “[a]ll Open Source communities should encourage software free-riders.”8 So far, we have a good distinction since the model no longer mistakes free riders as consumers of a non-excludable, non-rivalrous good. What’s rivalrous in this model is not the software, but the user. Although the taker makes use of the software, in this model it’s not the software that the taker is causing harm by taking, it’s the customer.

What’s rivalrous in this model is not the software, but the user. Although the taker makes use of the software, in this model it’s not the software that the taker is causing harm by taking, it’s the customer.

He goes on to say that when the project depends largely on one or more corporate sponsors, the community “should not forget or ignore that customers are a common good.” In other words, they must bear in mind that they themselves are a limited resource, and it matters who they support through purchasing decisions based on the assumption that “a customer can’t be shared among companies”, so purchasing from a maker indirectly supports the project in a way that purchasing from a taker does not. “In other words, Open Source communities should find ways to route customers to Makers.”

Here Dries places a limitation on free riding:

Both volunteer-driven and sponsorship-driven Open Source communities should encourage software free-riders, but sponsorship-driven Open Source communities should discourage customer free-riders.

This is significant because it implies that if the project is not highly dependent on sponsored contributions, it has nothing to fear from Takers, but this is not an avenue he explores.

Qualifying Takers

Let’s pause to summarize some qualifiers. Under the scenario being described, in order for the taker to actually be harming the maker in some fashion, certain criteria must be met.

- The maker and the taker must be in direct competition for the customer.

If they are not offering the same product or service, they aren’t in competition for the customer. The taker might be drawing money from the ecosystem, but it isn’t taken in a way that harms the maker, nor (necessarily) the wider community or the ecosystem generally. - The customer must choose between supporting the maker or the taker, not both.

Here the harm caused by the taker is in diverting resources (usually monetary) that would otherwise go to the maker, where some portion of the revenue will support maintenance of the software. - There must be a limited number of customers available.

If the number of customers is growing or is large enough that the maker couldn’t serve them all, then the taker’s activity must be excused. Either the taker isn’t diverting resources that the maker could have captured, or the customer/user pool is expanding, meaning they are not in fact a limited resource, and cease to be a rivalrous good. In fact, if the taker’s customers are new users, they aren’t takers at all – until the taker convinced the customer to become a user, they weren’t even in the pool. In this case, since the user is an anti-rival good, the taker becomes a maker in the sense that they are contributing by growing the network value of the software, the community of users, and the ecosystem they support. - The maker must be seen to have some claim to the customer.

You have to assume the maker has a right to claim the customer for themself rather than allow the taker to serve them. The argument implies that a right of this sort does exist, though in reality it may be more of a social contract than an ethical claim. The concept that the user owes allegiance to the maker over the taker essentially asserts that the maker is entitled to the customer.9 - The taker must be able to contribute but chooses not to.

Part of the taker definition, this can be problematic in that the taker’s financial situation or available skillset may not be nearly transparent enough to assess whether or not a company is actually a taker. This particular criteria for qualifying a taker is inherently vague, and a matter of external perception, making any judgment highly suspect, potentially no more accurate than guesswork. This doesn’t technically invalidate the premise, just renders it unknowable.

To complicate matters further, if the maker is late to market with a service that the taker is already providing, do users suddenly owe a duty to the maker to abandon their current vendor? Was the taker not a taker until the maker issued a competing offer? With free software, it’s easy to think of this as a hosting product, but it could also be support services or software add-ons. If the maker is in some way entitled to the revenue for his product, then his launch of a supporting service can bankrupt other community members or parts of the ecosystem, which is hardly a healthy position.

We could argue that the maker should consider their position toward the ecosystem in the way that a manufacturer must manage its dealer network: the ecosystem must be nurtured.

While rarely mentioned in a FOSS context, the issue may also be raised that the maker should consider his position toward the ecosystem in the way that a manufacturer views a dealer network. In order to maintain that relationship and build trust, launching products that compete with ecosystem contributors or taking advantage of their position as maker in the market can destabilize and harm the ecosystem.10 The uncertainty caused can discourage new entrants and force existing members to diversify outside of the ecosystem, stunting its growth. For this reason, a maker must view takers – like other users – as contributors to the growth of the ecosystem and its users.

Two things could dismiss the problem. If the taker contributes or sponsors in some fashion, it really only changes the label but with no guarantee of addressing the funding issue. Since we prefer to excuse companies that do not have the means to contribute, we must recognize that many takers are already mislabeled as such, with their financial ability to contribute not always a matter of public record or accurate perception.

The second is if the taker does not offer a competing service, in which case they aren’t diverting revenue that the maker could have captured. In that scenario, if the taker isn’t sponsoring or contributing to the software, it might be bad manners but it doesn’t actually cause harm to the maker. What we see toward those companies in practice can often be characterized as “hard feelings” that someone else is profiting from the ecosystem without visibly contributing to the software at its center.

In the maker-taker problem, users are valued in direct economic terms rather than for the network value they create to fuel the ecosystem.

The fundamental issue at play is ensuring that the maker has a revenue model adequate to support the ongoing work. This doesn’t sound very insightful, but the problem can be approached differently now that we’ve realized that (1) tragedy is not inevitable, (2) users are an anti-rival resource, and (3) free riders a positive influence. To our list, we add the fact that maker vulnerability to takers can be determined by inadequate or competing revenue models as much as simply by the behaviour of the taker. Most models draw a straight line between cause and effect, but in the end, it’s not quite as simple. This isn’t to suggest we’ve dismissed the whole problem, just that we’ve got a clearer picture.

At this stage, we can also point out that the maker’s need is inherently presumed to be financial throughout the explanation of the problem. While I’m certain Dries recognizes other needs, the entire premise tends to hinge on this point. As a result, users are valued only in economic terms, and not for the network value they create to fuel the ecosystem.

Back to the Commons

Going deeper into the model’s foundation, we return to Dries’ descriptions of the maker-taker problem, where he writes,

Studying the work of Garrett Hardin (Tragedy of the Commons), the Prisoner’s Dilemma, Mancur Olson (Collective Action) and Elinor Ostrom’s core design principles for self-governance, a number of shared patterns emerge.

We’ve already seen how Ostrom’s work disproves the inevitability of Hardin’s thesis, and how his motivations for promoting the view are… questionable. When considering the free rider problem, we also saw that group cohesiveness diffuses the detrimental effects of the prisoner’s dilemma. We’ve recognized Ostrom’s authority on CPRs, or common-pool resources, noting its fit to free software is subject to some adjustment for non-rivalrous goods. We’ve not yet discussed Olson’s work, but other economic models have been shown to be deficient when describing free software. This brings us to Dries’ summary of these works together:

When applied to Open Source, I’d summarize them as follows:

- Common goods fail because of a failure to coordinate collective action. To scale and sustain an Open Source project, Open Source communities need to transition from individual, uncoordinated action to cooperative, coordinated action.

- Cooperative, coordinated action can be accomplished through privatization, centralization, or self-governance. All three work — and can even be mixed.

- Successful privatization, centralization, and self-governance all require clear rules around membership, appropriation rights, and contribution duties. In turn, this requires monitoring and enforcement, either by an external agent (centralization + privatization), a private agent (self-governance), or members of the group itself (self-governance).

Of these points, I think the first is a good observation that I’d agree with, as there’s no scale without coordination. The second point lists three valid models which have all been shown to be effective. It may be up for discussion how successfully they can be mixed without becoming competitive, but this isn’t a concern for the present.

When contribution becomes a duty, the software is no longer free. It may still be open source, but it is not free — neither libre nor gratis.

The third summary point starts to go askew, likely impacted by the models we’ve already set aside. The point is correct in saying that all three approaches require clear rules (as Ostrom contends), but goes too far with the phrase “contribution duties.” This may be nuance on his part, but when contribution becomes a duty, the use of the software is no longer “free”. This may still fit many open source contexts, but runs counter to free software. The term “enforcement” applied to the previous phrase seals the deal as something contrary to free (libre) software under copyleft licenses like the GPL, MIT, and others that fundamentally seek not to restrict the use of the software (e.g., freedom zero of the GPL).11

This is where the maker-taker problem goes off the beam for free software, even while it may remain applicable for other kinds of open source. It therefore stands to reason that the post draws to a conclusion with three “[c]oncrete suggestions for scaling and sustaining Open Source,” his final suggestion is to experiment with new licenses. He offers some examples before suggesting we create new ones to “support the creation of Open Source projects with sustainable communities and sustainable businesses to support it.” There’s an assumption here that the revenue model is also a business model that the maker operates to fund development, but we should note this is not the only funding model.

Dries’ second suggestion is encouraging end users “to offer selective benefits to Makers.” His examples include making open source contribution a vendor selection criteria, but other forms could also apply.12 The first suggestion on his list is “Don’t just appeal to organizations’ self-interest, but also to their fairness principles.” On this point, I would say that “fairness” is an unstable concept, being both too subjective and too perspective-based to be a reliable measure. In a corporate context, “fairness” is quite easily exchanged for competitive advantage. Instead I would substitute the concept of community responsibility, or that of a social contract.

With the Maker-Taker problem, Dries is right in things like his consideration of different kinds of goods and recognizing the value of free riders, but we still have some issues that force us to set aside its conclusions.

What Dries gets right with the Maker-Taker problem is his consideration of different kinds of goods and recognizing the value of free riders. Next, he locates the problem as one of conflicting or competitive revenue models and funding the ongoing cost of development. I appreciate his stipulation that takers are not simply those who don’t contribute, but those who don’t contribute even though they have the means to do so. This qualifier is very helpful and is missing from every other model we’ve considered. Dries’ model offers the insight that the “taker” label should not be an absolute. He even provides an example of a software project from which his company benefits without contributing, yet it’s clear that his company does believe in OSS, and contributes to other FOSS projects.

Our issues with the Maker-Taker Problem are these:

- While it has some application to open source, it is less applicable to free software.

- It makes some fundamental assumptions about revenue models that are not consistently accurate.

- It sets a course toward enforcing contribution.

- It tends to assert some kind of “first right of refusal” on customers to the maker. This is an assertion of entitlement that can support rent-seeking rather than profit-seeking.

- It discounts alternate forms of contribution by the “taker”, including user recruitment.

- It assumes customers (a subset of users) are a limited-pool resource.

That said, Dries’ description of the “Maker-Taker Problem” is the most closely-fitting explanation we have so far concerning the challenges of funding FOSS development. Its name is somewhat unfortunate, as the title without the longer explanation implies an association with the free rider problem that Dries himself rejects.

Collective Action (Logically)

Mancur Olson argues that rational, self-interested individuals will not voluntarily contribute to large group efforts without selective incentives or coercion.

This leaves us with one loose end: Mancur Olson’s The Logic of Collective Action. Writing in 1965, before Garrett Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons” and Elinor Ostrom’s later work on CPRs, Olson argues that rational, self-interested individuals will not voluntarily contribute to large group efforts without selective incentives or coercion. We’ve outlined problems with rational self-interest that warn against its application to economics, and have seen that free software keeps breaking the assumptions.

Like Ostrom, Hardin, and the game theory models we’ve looked at, Olson is not specifically addressing FOSS communities, but is addressing collective action by groups in a broader way. In Olson’s view, since the benefits of collective action are non-excludable, it creates a free rider problem. Our context challenges the assumption that the resource is rivalrous, and therefore dismisses the free rider problem due to the near-zero distribution cost of an anti-rival resource. (This is in line with Dries’ description as well.) Olson contends that small groups can organize more effectively than large ones due to the logistics and cost of organizing and coordinating their effort, and suggests a greater individual return on effort exists in a smaller group.

From his vantage point in 1965, Olson could not possibly have foreseen the internet and its impact upon collective action, so we must apply those more recent realities to the principles he outlines in order to determine what might remain applicable to the present context. The internet fundamentally disrupted the cost of contribution and ease of coordination while enabling broader forms of recognition. In addition to the increased size of the pool from which to draw motivated contributors, the internet and an increasing ease of applying technology to problems have helped FOSS projects defy Olson’s conclusions, entirely flipping the script. As Steven Weber writes,

The twist is this: Under conditions of antirivalness, as the size of the Internet-connected group increases, and there is a heterogeneous distribution of motivations with people who have a high level of interest and some resources to invest, then the large group is more likely, all things being equal, to provide the good than is a small group.

Since we can easily cite a variety of large software projects which defy Olson’s logic, we could simply apply Ostrom’s law to say that since it works in practice, it must also work in theory. What we see here is that the internet is a fundamental game-changer that upsets the idea that large-scale collaboration is too difficult to be achievable.

A New Bottom Line

Circling back to the maker-taker problem, we’ve now illustrated that its underlying source material is not directly applicable to free software without significant modification. The fundamental assumptions underlying the maker-taker model generally mean that we cannot accept it as fully valid, in particular with respect to free software projects with development organized online. That said, we’ve also seen that while it does exist in certain FOSS ecosystems, it doesn’t have to — at least not for reasons other than demanding contribution. In other words, the problem does not exist where the software project is not reliant upon a revenue model that is impacted by direct competition. It’s still fair to say that Dries’ description of the maker-taker problem is the most considered of all the models we’ve looked at, even if we ultimately need to set it aside in search of a better description of a problem with an appropriate solution.

All of the models we’ve considered deal with concerns over the “undesirable” behaviours of other people and the attempt to regulate that behaviour.

All of the economic models we’ve considered, both the description of the problem and the proposed solution fairly consistently deal with concerns over anticipating the “undesirable” behaviours of other people and the attempt to modify or regulate that behaviour. But what if — and hear me out — the problems could be defined without focusing on the actions of others, and the solutions were things within our own control? If these perceived problems could be resolved without attempting to control the behaviour of others, what then?

We’re left now without an adequate description of an assumed problem of sustaining FOSS development. To come up with one, we’ll need to test the assumption that there is a problem, describe it without reliance on older economic, behavioural, or organizational models, and if necessary, derive a solution that does not placing a burden of directing or restricting the behaviour (i.e., freedom) of others. Such a solution would give the FOSS project the power of self-determination. Certainly many projects have resolved any issues to their own satisfaction, even if that solution is based in an imperfect model. The issue with those is the temptation to replicate that solution to a project which assumes a problem which may not exist in the way it was presumed.

Where do You Share?

Notes

[footnotes_block]Works Cited & Further Reading

- Barr, Joe. “Live and let license” Linux World, 2001-05-23

- Buytaert, Dries. “Balancing Makers and Takers to scale and sustain Open Source“, 2019-09-19.

- ______________. “A cure for unfair competition in open source”, (Part 1) InfoWorld, 2019-11-06.

- ______________. “How takers hurt makers in open source“, (Part 2) InfoWorld, 2019-11-06.

- ______________. “Open source and the free-rider problem“, (Part 3) InfoWorld, 2019-11-06.

- ______________. “Solving the Maker-Taker problem“, 2024-10-02.

- De Valk, Joost. “The two faces of WordPress: and why that’s a problem”, 2025-05-25.

- Kooyman, Zoë. “Free Software and Why the Terms Matter” (video presentation, June 2025)

- Olson, Mancur. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard University Press, 1965. PDF.

- Stallman, Richard. “Why Open Source Misses the Point of Free Software” (FSF, n.d.)

Various or Unspecified Authors

- “Community (ecology)“, Wikipedia, Wikipedia, accessed June 2025.

- “Ecosystem“, Wikipedia, Wikipedia, accessed June 2025.

- “Ecovilliage“, WIkipedia, Wikipedia, accessed June 2025.

- “Source-Available Software“, Wikipedia, accessed June 2025.

- “The Logic of Collective Action“, Wikipedia, accessed June 2025.

Cited from this Site

- Toderash, Brent. “Unmasking the Tragedy of the Commons”, 2024-10-23.

- ________________. “Methodological Individualism & the Rational Individual“, 2025-01-02.

- ________________. “Free-Riding Free Software“, 2025-01-03.

Notes

- Stallman (aka “RMS”) developed the GPL and founded the Free Software Foundation. Raymond (aka “ESR”) co-founded the Open Source Initiative and wrote one of the defining works of the movement, The Cathedral and the Bazaar.

The phrase “open source” was first coined in February 1998 by Christine Peterson, and while it was widely adopted fairly quickly, Stallman hated it for dropping the emphasis on freedom and contended that Open Source Misses the Point of Free Software. The argument mostly died down through the mid-2000s, but would still flare up on occasion.

- In the field of ecology, what we refer to as “community” may be closer to an “ecovillage”.

- The distinction is decidedly not a pejorative one. Every piece of software — open or not — has always had a group of users. As we saw when considering free riders, without users, software has no value. Without users, the the growth potential of the ecosystem will remain limited.

- For example, those using ecommerce software to sell goods or services having nothing to do with the software itself or its ecosystem.

- Dries Buytaert, “Solving the Maker-Taker problem”, October 2024.

- I’m going to quote liberally from Dries Buytaert’s two posts on this subject, “Balancing Makers and Takers to scale and sustain Open Source“ (September 2019) and “Solving the Maker-Taker problem” (October 2024), and attempt to summarize his position here.

- Since the example compares a single maker with a single taker, a missing factor is the value of volunteer contributions from other makers, from which both benefit more or less equally. This reduces the delta between the numbers, but doesn’t invalidate his point.

- Emphasis his.

- There are a number of downsides to this. First, notions of entitlement in practically every form are toxic to a community. Second, in this kind of ecosystem, users lose their freedom of vendor choice, effectively removing a freedom that they expect to enjoy in a FOSS environment. Third, unless another non-taker is also providing the service, the customer must accept the business risk of a service the customer may upon being available from a sole source.

- In contrast, through the “Microsoft Era” of computer operating systems, many software vendors went dark as Windows simply added a new feature to their product. Some of them were acquired, others not so much. When Microsoft added file compression into Windows, companies like PKzip had to pivot while others like Netscape became victims of antitrust misdeeds.

- We might note that where someone takes issue with this as not being “fair”, the issue isn’t really about equity, it’s an issue with copyleft licensing. If one holds these values, an open source but non-copyleft license would be far more palatable, as the perceived “fairness” can more easily be enforced through the license terms. Essentially, this is a measure of how committed one may be to “Freedom 0” of the GPL.

- When VA Linux and Red Hat were approaching their IPOs, they both gifted shares to Linus Torvalds in recognition of his creation of and work on the Linux Kernel.