Methodological Individualism & the Rational Individual

Abstract

Most of the economic theory we operate under today dates back to Adam Smith in 1776. Smith made a fundamental assumption about individuals being motivated by self-interest, and used this motivation as a predictor for free market economic theory. Much of what was later based on Smith’s work miscasts his views somewhat, but for the past 250 years, the core assumption about individual motivations predicting group behaviour have been left largely unchallenged within our common conception and practice of economics. The assumption has been challenged and largely displaced in the academic study of economics, as well as several different angles within the social sciences, cultural disciplines, and network effects. Foundational theories like methodological individualism, rational choice theory, and the rational individual must be removed from their foundational place in our economic theory. These not only lead us to false conclusions about how our economic models work, but causes our group behaviours to shift. With these assumptions being found lacking in their initial intended applications, they are even less suited to explain the economics of open source software and our understanding of the nature of the communities which produce it.

Embarking on an Excursus

This article is essentially what in academia, we call an excursus, which is not exactly a “rabbit-trail,” as an excursus generally has a point relevant to the main argument, but requires a tangential discussion in order to establish. Hence, “going off on a tangent.” If the excursus wasn’t somehow relevant to the main argument, it would generally be cut from the work as off-topic. Thus while this subject may look off-topic at first blush, it establishes a point that will be important later. With that in mind, the material can often be skipped until the point comes up, and if the reader wishes, they can review the tangential material to evaluate it more deeply.

Here, we will consider a basic assumption about human nature, motivations, and behaviour that we’ve already seen when unmasking Garrett Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons”. It will come up again in the free rider problem, which we will be reviewing next, and yet again in a future piece on the hacker ethic. For that reason, we’ll explore it here to be able to save some time later. There’s some fascinating trains of thought here, but if you get to the end of the key concepts section and decide that the theories there can be rejected outright, you’ll have already reached the conclusion of the essay and may just want to review some highlights for academic interest or to see details of what’s wrong with those concepts and what it means for some common economic theories.

Prologue: Hardin’s Assumption

As we concluded our look at Hardin’s tragedy of the commons in the of his other works and ideologies, we saw some political and economic assumptions upon which his ideas were based, and which are shared in some of the circles where his views continue to find favour, whether broadly (racism and xenophobia) or limited to free-market economics.

Leaning on the analysis of David Bollier,1 I wrote in the closing section,

Viewing Hardin’s essay like a gospel parable affirming core principles of neoliberal economic ideology such as the importance of “free markets” and justification of the property rights of the wealthy[,] bolstering commitment to private property and individual rights as the cornerstone of economic thought and policy.

and

In the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, the economic mindset conveyed by Hardin’s essay prompted Wall Street to maximize private gain without regard for systemic risk or local impact. “The real tragedy precipitated by “rational” individualism is not the tragedy of the commons, but the tragedy of the market.”

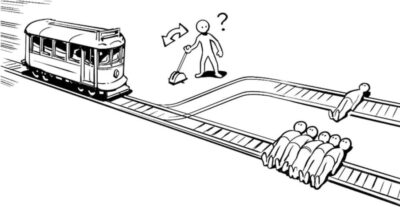

And there we have it, named in passing: “rational individualism,” with some shade thrown upon how rational this form of individualism truly is. From here, we’ll explore rational choice theory, motivational assumptions, the ability of individuals to make rational choices (whether rational for the group or the individual), factors in decision-making, and the impact of all these factors in economic theory, moral philosophy, and psychology. Clearly this is a tall order, so we’ll be taking a survey approach, during which we’ll visit the familiar prisoner’s dilemma and the trolley problem. We begin by defining our terms, and then unpacking their significance.

Philosophical Frameworks

Key Concepts

Methodological Individualism

Methodological Individualism says that individuals are the primary actors in shaping social outcomes.

Methodological individualism asserts that individuals are the primary actors in shaping social outcomes, establishing a philosophical approach to explain social phenomena by reducing them to the actions and motivations of individuals. As such, all social structures, institutions, and processes arise from the interactions and choices of individuals. In methodological individualism, the “elementary unit of social life is the individual human action”.2

Applied to economics, this means that market forces of supply and demand, rather than being nebulous or autonomous forces, are the result of numerous individuals each making their own buying and selling decisions.

Rational Choice Theory

Rational Choice Theory says individuals act in a rational self-interested manner.

While methodological individualism does not presume a specific model of individual behaviour, rational choice theory builds upon it with the assumption that individuals will act in a rational, self-interested manner in their decision-making.

This contrasts with other approaches within methodological individualism, which might focus on other motivation, such as emotions or habits, social norms and values, or the social structures which arise from and then act to constrain individual choices. Any of these may act to cause a departure from the purely rational decisions assumed by rational choice theory. 3. Also known as rational individualism, this is where we find our “rational individual,” and must determine whether he be mythical or material.

The Rational Individual

The Rational Choice Model says individuals calculate maximum net benefit in making choices.

The rational choice model assumes that individuals make decisions by evaluating the costs and benefits of various options and choosing the one that maximizes their net benefit. The theory requires that individuals must be capable of identifying and weighing different options presumably with some degree of accuracy, though this is not a strict requirement in the model. Fundamentally, the theory posits that their choices are motivated by a desire to achieve the best possible outcome.

From here, the theory diverges somewhat, with one set of adherents suggesting that individuals are inherently self-interested and will evaluate available options in terms of what is the most desirable for them personally. On the other hand, a more moderate application of the theory acknowledges that individuals can be motivated by a variety of factors, including altruism or social approval, which might be realized through an option which is not the most personally advantageous one.4

Either version of the theory tends to place the individual at the center, explaining social phenomena as the sum of rational calculations made by self-interested individuals. Social interaction in this view is an economic-styled exchange, with people motivated by net gain (profit) after accounting for its costs and benefits.5 Even when proponents of this theory of rational individuals acknowledge a complex set of factors in decision-making, the core consideration remains that of self-interest both in social and economic terms, with emphasis on the latter.

An Idea to Be Retired?

In 2014, Edge.org posed a question: “What scientific idea is ready for retirement?” Among the responses, the idea of the rational individual was named as due for retirement.6 Suggesting that the research doesn’t bear out the theory, he writes,

[W]e are now coming to realize that human behavior is determined as much by social context as by rational thinking or individual desires. Rationality, as economists use the term, means that an individual knows what he or she wants and acts to get it. But this new research shows that in this regard, social network effects often, and perhaps typically, dominate both the desires and the decisions about how individuals act.

Motivations stem from a complex set of factors, but are still only a subset of factors in deciding upon a course of action. In some of these, it requires the actions of others as a precursor for an individual to entertain taking the same action. At times, these actions must be cooperative or collective in nature.

Our desires and preferences are mostly based on what our peer community agrees is valuable, rather than on rational reflection based directly on our individual biological drives or inborn morals.

For instance, after the Great Recession of 2008, when many houses were suddenly worth less than their mortgages, researchers found that it only took a few people walking away from their houses and mortgages to convince many of their neighbors to do the same thing. A behavior that had previously been thought nearly criminal or immoral, i.e., purposely defaulting on a mortgage, now became common. Using the terminology of economics, in most things we are collectively rational, and only in some areas are we individually rational.7

Pentland’s point is that the determination is not made as a strictly individual consideration, but can be heavily influenced by group action.

Test Your Assumptions

It’s not difficult to see (and should come as no surprise) that these assessments of basic human nature, their effect on individual decision-making, and the resulting collective effect of a group of individual decisions is far from simple. Yet as we’ll see, we have a lot of accepted theory banking on having made the right assessment of these factors as social and economic models are layered on top of them.8

In economic theory, an assumption about self-interest is extrapolated to predict individual behaviour and its collective economic impact. But what if it’s wrong?

In writing on the tragedy of the commons, I said,

Building policy on such flawed assumptions causes real and lasting harm. For example, John Locke was used to justify treating the New World as terra nullius—open, unowned land—even though it was populated by millions of Indigenous people who “managed their natural resources as beloved commons with unwritten but highly sophisticated rules.”9

We will do well to test our assumptions, and not just once, but to revisit them periodically in light of all that we’ve learned since the assumption was first formed.

¼ Millennium & Nothing is New

In a surprising number of places, we’ll find that some major political ideologies and economic theory is based not in mathematics, morals, or ethics, but in an assumption about human nature. In these cases, some significant models and overarching ideals are built upon conclusions that social psychologists aren’t necessarily ready to sign off on. (This should surprise us more than it likely will.)

Failing to understand how one human will act means failing to understand how the group will act, and thus failing to correctly anticipate the economic impact of those combined actions. There’s much that is predictable with demographics, but when one has to account for inner motivations, especially under duress and with myriad external circumstances pressing, all bets are off.

Hardin picked up a then-135-year-old essay by Rev. William Forster and found a theory he could run with, as its assumptions fit well enough with his own. But it didn’t start with Forster: looking back a little further, we find a seminal work on economic theory from 1776 built upon very similar assumptions rooted in an earlier work on ethics by the same author. Together, they show that capitalism itself is deeply rooted ion methodological individualism and rational choice theory.10

Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments

Adam Smith (Scotland, 1723-1790) is described as an economist and philosopher, and regarded by some as the “Father of Economics” or the “Father of Capitalism”. His 1776 magnum opus was An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, where in reaction to the mercantile system, he described what has become the foundation of free-market economic theory. The work presents a theory of how competition, the division of labour, and “rational self-interest” lead to prosperity.

Although he is best known as an economist, Smith was also a philosopher, and in particular, an ethicist. In 1759, he wrote The Theory of Moral Sentiments, where we find some of his views on the behaviour and motivation of individuals that eventually form some of the underpinnings of his economic theory. He wrote that the rich “consume little more than the poor” and while seeking their own self-interest, in employing of the labour of others

they divide with the poor the produce of all their improvements. They are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants, and thus without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of the society, and afford means to the multiplication of the species.11

If this sounds a bit like the aphorism that “a rising tide floats all boats”, or rings with an echo of “trickle-down” (supply-side) economics, you’ve likely understood Smith’s point well enough.

Age of Enlightenment Economics

Having seen how Smith’s ethical notions presumed a grounding in self-interest, we now turn to his economic theories that followed in 1776, beginning with an early influence.

The Physiocrat were, a group of French economists who held that wealth derived solely from land and emphasized productive work as the source of national wealth. For them, productive work was agricultural labour only. For them, commerce and manufacturing labour was “sterile”, transforming raw materials without adding value. Smith rejected this narrow view of labour, arguing that these sectors contribute to the economy by replacing the value of their consumption and the capital that employs them. Drawing a marital analogy, he observed that even if a couple produces only two children to replace themselves, the marriage could not be considered barren.12

The Physiocrats believed self-interest to be the primary driver of the economy — that individuals working in their own self-interest would create wealth for all.

As a reaction against mercantilism, the Physiocrats were strong not only on free trade, but on private property and investment capital. They viewed self-interest as the motivation that drove the economy, with individuals working toward their own interests creating wealth for all as the natural by-product of those pursuits. This individualism held that while someone’s labour might be undertaken to benefit others, they would work harder if it was to their own benefit. With the individual as the center and government restrictions seen as an undue hardship, we find in Physiocracy the nucleus of laissez-faire economics. Smith was more influence by this line of thought.

Smith’s Wealth of Nations

Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations is seen as the foundational treatise for classical economic theory. Here we discover here that Smith has based his economic theory on his moral one. Hailed as a founding father of capitalism, Smith builds an economic model on the the primacy of self-interest as an economic motivator, consistent with the Physicoratic view of the individual and with what would later be described as methodological individualism. In Smith’s view, markets would coordinate naturally around individual self-interest to somehow, under the influence of “an invisible hand” combine for the public good. As noted above, Smith argued that this method of arriving at the common good would be as effective as if all public goods had been equally divided all along.13

In Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith had introduced “sympathy” (his term, but more accurately, empathy) as a foundational social mechanism, saying that because people have an innate capacity to imagine themselves in others’ positions, pure self-interest is subject to self-moderation. In Wealth of Nations, he argues that self-interest paradoxically produces collective benefit through the “invisible hand” such that individuals pursuing their own economic goals inadvertently create societal wealth for everyone.

In a review of two books on Smith’s legacy for capitalism, Vivienne Brown wrote in The Economic Journal that Reaganomics supporters, The Wall Street Journal, and similar sources have spread a misleading representation of Smith as an “extreme dogmatic defender of laissez-faire capitalism and supply-side economics”.14 Indeed, Smith was not entirely a laissez-faire capitalist in the model of the Physiocrats, espousing as he did certain limitations to the free market. Smith saw the role of government as including not only enforcement of regulations, but building and maintaining infrastructure.15

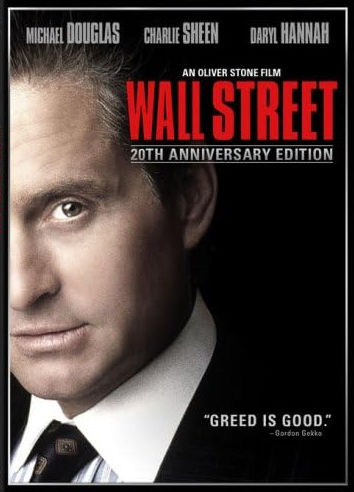

Many later proponents of Smith’s economic theories would remove the limitations and nuance found in his original work to misrepresent his position. With or without governmental limitation, the core assumption about human nature remains, with Smith’s views being consistent with those of the Physiocrats and what we would later call rational choice theory, a subset of methodological individualism against which proponents like Max Weber had cautioned. Despite how Smith’s work is framed by libertarians, laissez-faire capitalists, and others, Smith recognized the need for limits. Some of these, we could argue, are necessitated by the very thing upon which the theory revolves: greed. Without limitation, self-interest is greed, and greed limited is not a true form since it recognizes that the needs of others may outweigh one’s own self-interest, and require actions which are not to one’s own advantage.

The Children of Gordon Gekko

Smith argues that by seeking their own self-interest, the rich improve the economy to the betterment of the poor, and thus it is normal, rational, and productive to the advantage of all to behave in one’s own self-interest. The various terms that have been used — supply-side economics, “Reaganomics,” “trickle-down” economics, and laissez-faire capitalism among others all make the suggestion that by pursuing their own economic self-interest, the wealthy are the market-drivers who improve the economy for everyone’s benefit, including that of the poor.

The 1980s gave us “Reaganomics“, and by the end of the decade, we had an emblematicly-memorable Hollywood character16 who would have approved. As Gordon Gekko summed up the argument in a climactic speech to a roomful of shareholders, “Greed is good.”17 With a powerful delivery by Michael Douglas, Gekko’s snappy line in the movie Wall Street became a more famous expression of the zeitgeist of the 1980s than that of real-life arbitrageur Ivan Boesky, when in his 1986 commencement address to the School of Business Administration at University of California Berkeley, he opined, “Greed is all right, by the way. I want you to know that. I think greed is healthy.” Gekko was partially based on Boesky, and in case anyone forgot, Gekko was the villain of the story. His famous “Greed is Good” speech was meant as an indictment, and would later be used as the rhetorical backdrop to explain the cause of the 2008 financial crisis by Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd (“The Children of Gordon Gekko”) and Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone addressing the Italian Senate.

Despite what we teach our children concerning one of the Seven Deadly Sins, we choose not only to reject the lesson ourselves, but to build a society on the notion that this is not a moral failing, but a positive outcome to be recommended for societal benefit.

It shouldn’t need to be said that greed is in fact not good, as is universally taught to children in guiding them to grow into moral adults. Yet our prevailing economic theory is solidly rooted in the idea not just that everyone will act in their own interests, but that they should, and that this self-interest produces the most good not just for ourselves, but for others as well. In other words, despite what we take as an axiomatic truth concerning one of the “Seven Deadly Sins,” we later choose not just to reject the lesson ourselves, but to build a society on the notion that selfishness is not a moral failing, but a positive outcome to be recommended for societal benefit.

While we may not be able to deny that self-interest has a role in determining some of our own actions, our morals and ethics also have a role to play, along with myriad other considerations. To imagine that self-interest always takes precedence in most situations seems something of a stretch.

The “Me First” Values System

Our survey so far demonstrates that a core part of many longstanding theories and thought experiments include a flawed belief that individuals’ decisions are fundamentally based in self-interest. At some point, the word “narcissism” comes to mind. The connection is demanded by the assumed universality of self-interest and the accepted degree to which people can be counted upon to choose selfish over altruistic actions with acceptance of a value system that prizes individual and personal interests ahead of others.

We find common acceptance of a “me-first” value system as not only reasonable or responsible, but rational and beneficial, proposing that a healthy and prosperous society is best comprised of individuals acting in their own self-interest rather than acting in or even attempting to understand what is best for that society as a whole.

This “me-first” values system is regarded as not only reasonable or responsible, but rational and beneficial, with the proposition that a healthy and prosperous society is best comprised of individuals acting in their own self-interest rather than acting in or even attempting to understand what is best for that society as a whole. For the group, it is expected that things will simply “work out” somehow. One might expect this type of thinking from the “Me Generation”, but we’ve seen that it dates to at least a couple of centuries before.

Social critic Christopher Lasch contended that modern capitalism has produced a narcissistic personality structure that erodes community and social bonds.18 Although his discussion of a narcissistic culture might tend to support the notion of simple self-interest as primary motivation, his discussion of it makes clear that he places an emphasis on multilayered social dynamics, being critical of reductive economic and psychological models. Lasch asserted that individualism had mutated from self-reliance to self-absorption, and although his primary target was narcissism produced by capitalism-driven consumer culture, his work has a direct bearing on our consideration of individualism at the heart of economic theory and social sciences.

Inadvertently Altruistic?

Smith, Weber, & Dawkins

Smith may not have been the best ethicist, seemingly unable to come up with a valid motivation for altruistic behaviour. His description of an “invisible hand” that guides people who act in their own self-interest to inadvertently act at the same time in the common interest might seem almost quaint and easily dismissible, except that it now has 250 years of economic theory built on top of it. To be fair to Smith, a lot of that theory misinterprets or misrepresents his actual views. Outside of economics, any understanding of individual motivation is viewed as anything but simple, rational, primarily mathematical, or highly predictable.

In The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins suggests that apparent altruistic behavior be examined through the lens not of economic but genetic self-interest.

Rather than rely upon an unseen or inexplicable hand, in The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins suggests that apparent altruistic behavior be examined through the lens not of economic but genetic self-interest. He sees cooperative behaviour evolving because they ultimately benefit the genes of the individual more than does competitive behaviour. Dawkins sees cooperative behaviour as motivated by altruism, but by a sophisticated survival mechanism. He models how complex cooperative behaviours can emerge from simple genetic self-interest, but stipulates that this doesn’t justify selfish behaviour since we can actively choose to act differently. Dawkins faced criticism over whether the characteristic of selfishness could be applied to genes and whether he had described too simplistic a view of complex biological factors.

What’s interesting about Dawkins is that writing well over two centuries apart and based in quite different trains of logical thought, Smith and Dawkins both recognize that individual motivations may be heavily influenced by group outcomes while simultaneously attempting to explain “apparent” altruism by any means other than intrinsic motivation, attempting to root altruism in selfishness.

Max Weber argued that behavioural motivation has cultural and religious frameworks.

Weber gave us methodological individualism, but cautioned against an individualistic system of values.

In the early 20th century, Max Weber argued19 that behavioural motivation isn’t purely about material gain, but has a cultural and religious frameworks that value the work itself as morally good. It was Weber in 1922 who introduced and defended the concept of methodological individualism in Economy and Society, where he also cautioned that “it is a tremendous misunderstanding to think that an ‘individualistic’ method should involve what is in any conceivable sense an individualistic system of values.” His caution wouldn’t stick, with theories of “individualistic values” being asserted particularly in the 1950s and 1980s to give us the concept of “rational individualism.”

Hackers, Networks, & Narcissists

The “hacker ethic“20 reframes Weber’s non-monetary value of work as being about about passion, creativity, and collective knowledge production. Recognizing a profound difference in digital spaces, Yochai Benkler proffered an update to Ronald Coase’s theory of the firm,21 arguing that peer production systems like Linux challenged traditional economic theories about why firms exist, suggesting that people driven by factors like reputation, learning opportunities, and a desire to contribute to public goods would contribute to open projects without direct monetary incentives, with digital platforms enabling large-scale cooperation without the necessity of economic incentives.

The ease of online collaboration began to reveal challenges for behavioural assumptions and economic theory.

In Here Comes Everybody, Clay Shirky applies these principles to online communities where low transaction costs and networked technologies facilitate unprecedented forms of collaborative action, with individual self-interest being transformed by the very platforms that make collaboration both easier and more beneficial than competition.

Using AI to generate a hypothetical summary produces the suggestion that if all these thinkers were (somehow) in a dialogue together, they might jointly argue that

Individual actions are not simply about immediate self-interest, but about complex interactions between personal motivation, cultural frameworks, technological possibilities, and emergent collective behaviours. The ‘self’ is not a fixed economic actor, but a dynamic node in increasingly sophisticated networks of cooperation and exchange.

The AI model went on to create the following overview:

The beauty of these perspectives is how they progressively deconstruct a simplistic view of self-interest:

- Smith shows self-interest can produce collective benefits

- Weber reveals self-interest is culturally mediated

- Dawkins demonstrates genetic “self-interest” can produce apparently altruistic behaviors

- Benkler shows digital platforms can reshape individual motivation

- Shirky illustrates how technology can make cooperation more efficient than individual action

This is a good summation. Of course, it’s just a cursory overview of a few significant voices offering perspectives on a subject for which much larger body of work exists to discuss the complexity of individual motivations and how they may prefer interaction and cooperation even over actions that would be demanded by simpler forms of self-interest.

Christopher Lasch’s work challenges a simplistic model of rational choice theory by demonstrating how psychological structures shape economic behaviour. His critiques were similar to Yochai Benkler’s views of collective action, although his cultural perspective is less optimistic than Benkler’s, perhaps in part because his major work predates the network benefits of the internet. His work shows that individual choices are never purely that, but are steeped in cultural as well as economic factors. Lasch’s work would suggest that the explanations we’ve looked at omit the crucial point that economic systems don’t just interact with psychological systems, they recursively generate them. In other words, we shape them, and then they shape us.

We’ll return to the hackers and their networks in a future article. To cap this overview and critique of individualism, we’ll add just two more sources that reflect serious academic approaches summarized in publications for a broader audience.

Steven Pinker & Daniel Kahneman

Named to numerous top-100 and top-10 lists of global influencers and thinkers since 2004, Steven Pinker‘s evolutionary psychology perspective would say rational choice theory misunderstands human motivation as being purely logical. In this view, individual choices are shaped by ancestral survival strategies rather than being reduced to immediate utility. In essence, we have a view of “the bigger picture”, which influences our choices. Cultural and evolutionary context will therefore be greater factors for us than abstract economic models will, since human rationality was adapted for survival rather than for peak economic (or for that matter any other) optimization.22

From cognitive psychology, Daniel Kahneman would suggest that rational choice theory assumes humans make consistently logical, utility-maximizing decisions, but he then demonstrates cognitive biases that fatally undermine the assumption, suggesting instead that we use “bounded rationality”. Using heuristics as mental shortcuts, we often deviate from pure rational logic calculation under the influence of an array of cognitive biases, and fallacies like confirmation bias, sunk cost fallacy, and prospect theory, a behavioural economic theory he co-authored. His work results in a systematic proof that our decision-making process has more to do with psychological influences than mathematical optimization.23

Daniel Kahneman was awarded a Nobel Prize in Economics for his empirical findings upsetting the assumption of human rationality in modern economic theory.

In 2002, Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for publishing empirical findings upsetting the assumption of human rationality in modern economic theory, for which some refer to him as the “grandfather of behavioural economics.” Kahneman’s work with Amos Tversky turned behavioural economics from the unfounded presupposition we have outlined into an actual field of study.

Just as it clung to Hardin’s premise of the tragedy of the commons long after it was exposed as foundationally wrong, the corner of economics represented by wealthy investors and politicians continues to hold to an economic model whose foundation has shifted under the weight of its failure to understand human motivation.

Game Theory in the 1980s

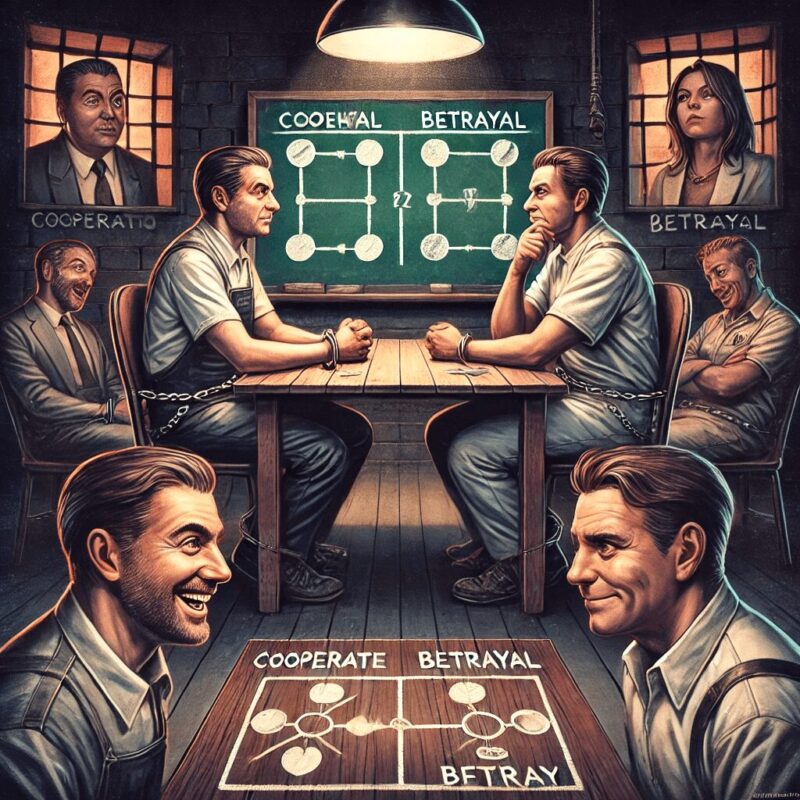

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

At the end of the move Wall Street, we find out (spoiler warning) that Gordon Gekko’s protege Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen) has turned on him and “worn a wire” to record Gekko’s confession to insider trading. Thus we have our segue to the prisoner’s dilemma. With clear oversimplification, interest in methodological individualism had been waning, until

the sudden explosion of interest in game theory (or “rational choice theory”) among social scientists in the 1980s. The reason for this can be summed up in two words (and an article): the prisoner’s dilemma. Social scientists had always been aware that individuals in groups are capable of getting stuck in patterns of collectively self-defeating behavior.24

Without delving deeply into the detailed mechanics of the exercise, the Prisoners’ Dilemma is a concept in game theory that plays individual interest against group interest as a means of demonstrating that even when cooperation is in their best interest, the players – in this case, prisoners – will decline to do so. Through a specific test, it is expected that people will put individual outcomes ahead of collective outcomes to choose what is deemed the “most rational” approach for the individual even though it results in a worse collective outcome for the group. In trope-like fashion, countless television shows play out the scenario with detectives arresting two criminals to see which will turn on the other first.25

The prisoner’s dilemma posits that if one individual assumes the others will act in their own self-interest above the interests of the group, they too will act in the same fashion in a preemptive or self-preserving manner, ensuring the worse outcome for the group.

Obviously, the prisoner’s dilemma doesn’t always work as described. Despite its similar assumption about decision motivators, the prisoner’s dilemma isn’t strictly presented as an inevitability in the way that the free rider problem and the tragedy of the commons have been, though it does expect the same outcome. This theory of self-interested action is no more assured here than we’d expect after our survey thus far. Sometimes neither criminal will cooperate with authorities due to an overriding group loyalty (or perhaps fear of reprisal). Among Mafiosi the term is Omertà, a well-known part of the lore. In these cases, the prisoner acts in the interest of the group rather than self. Disrupting the decision process doesn’t need anything nearly so forceful as organized crime, though. As Glenn Geher writes,

A simple rule of Prisoner’s Dilemma is this: When we play against someone else in an iterated manner, expecting to have further interactions with that same person, we tend to be nicer than when we are playing against someone in a one-off capacity.

The prisoner’s dilemma suggests that if one individual assumes the others will act in their own self-interest above the interests of the group, they too will act in the same fashion, in an essentially preemptive or self-preserving manner, assuring the worse outcome for the group, making the assumption about how others will act either a self-fulfilling prophecy or simply moot, depending which side you’re on. The bottom line though is that even the idea that we’ll have future contact with the other player creates a tendency to choose the better group result — not at all what we’ve been led to expect.

The Trolley Problem (Lifeboat Ethics)

In the Trolley Problem, we grapple with whether the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few,26 or of an individual. An obvious conclusion might be that the needs of the many clearly (logically, at least) do outweigh individual needs. fMRI scans done during presentation of different forms of the thought experiment indicate that its variations trigger different parts of the brain, which will presumably cause an individual to weigh certain factors differently in their decision-making process, so if nothing else, we can see it’s still not a simple equation, as much as that might make theoretical ethics discussions in the realm of robotics and self-driving cars much easier to resolve.

In a real-life version of Hardin’s “Lifeboat Ethics”, when the William Brown sank in 1841, 41 people found themselves in an overcrowded longboat. In order to reduce the load on the vessel down to its reasonable capacity and improve the chances of survival for most of the group, certain members of the crew forced 12 adult men overboard. For this action, the only crewman who could be located, Alexander Holmes, was tried for murder and convicted of manslaughter. Today, the case is used to frame discussions of “necessity” as a legal defence. It didn’t seem to work out for Holmes. It does raise the question – not answerable at this time or in this context – of whether the actions were those of self-interest for the preservation of their own lives, or of the interest of the larger group who remained in the boat compared with the number of those who were cast overboard. Herein lies the difficulty in accurately interpreting the motivations of another individual.27

With the assumption that people are going to act in their own self-interest, some degree of social engineering is often undertaken to incentivize people to act for the common good.

With the assumption that people are going to act in their own self-interest, some degree of social engineering is often undertaken to incentivize people to act for the common good by doing things that are in their own interest. The idea is that people will not act in the public or common interest unless it is also in their own interest, so the incentive is offered in such a manner that they will unwittingly act in the societal interest as they pursue their own.28 In both of his major works, Adam Smith wrote about examples of this tactic using the metaphor of “an invisible hand” (one instance of which is quoted above) guiding people to unintentionally act in the public interest. In Smith’s version, these acts are not ones of altruism, but accident.

Projections & Paranoia

Returning to the Prisoner’s Dilemma and the Tragedy of the Commons, we find that the fear of the thing presents a greater problem than actual thing.29 It’s the fear – or self-interest – itself that changes behaviour, causing issues for the ecosystem. To the extent that everyone trusts the other to act for the common good rather than individual self-interest, the system works just fine to benefit everyone. On the other hand, fear, suspicion, and pre-emptive behaviour-shifting undermines trust and breaks the system by becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. As Lasch described it, the assumption that everyone will act in a narcissistic manner actually causes the behaviour and shapes the system.

Fear, suspicion, and pre-emptive behaviour-shifting undermines trust and breaks the system.

This phenomenon is along the lines of what was observed by Richard Hofstadter in his famous 1964 essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”, where he outlined in a political context some of the various types of perception and attribution biases that were described in social psychology over the following decade. In Hofstadter’s explanation, we see politicians ascribing to an opponent the actions which they themselves might consider. What we see playing out is the presumption by one political actor that an opponent will definitely be engaged in some of the worst things that they themselves might entertain.30

This is where we find the source of that distorted approach to the Golden Rule, “Do unto others before they do unto you.” As we saw with the prisoner’s dilemma, modelling one’s behaviour after the less-desirable pattern expected of others in what is essentially a preemptive manner to preserve one’s self-interest makes the group effect another self-fulfilling prophecy. We act badly because we expect others to act badly, and when the resulting group outcome is negative, we then use that as justification for our actions, driving individual and group behaviour to gradually trend even worse.

It seems some people are seeking a form of “enforced fairness”, where they would rather something fails than risk contributing more than their perceived “fair share” without a guarantee that others will do the same. Fundamentally, it’s a mistrust that people will act in the interest of others, but it’s an open question whether that mistrust of others is warranted or if it’s just a projection of one’s own self-protective motivations onto others.

Climate change is a pertinent example, and is not infrequently used in this context. In response to perceived free riders who do not change their habits to combat climate change – cutting pollution or carbon emissions, for example – some individuals will decide that it’s not worth acting on their own since they would then bear the greater burden of combating climate change. This behaviour compounds the problem, since even fewer people act responsibly, modifying their behaviour based on their expectation of others’ bad behaviour. In the event of failure, rather than everyone being able to share the gain from the actions of some, the negative consequences are necessarily shared by all despite the preventative actions of a few.

In this, it seems some people are seeking a form of “enforced fairness”, where they would rather something fails than risk contributing more than their perceived “fair share” without a guarantee that others will do the same. Fundamentally, it’s a mistrust that people will act in the interest of others, but it’s an open question whether that mistrust of others is warranted or if it’s just a projection of one’s own self-protective motivations onto others. What is true is that the behaviour creates the condition to which it’s a reaction.

A Shaken Foundation

The fact is that people are for the most part just not that good at understanding the motivations behind the actions of others, and even worse at predicting what those actions will be based on those assumptions about motivations.

In all of these economic theories, we find a foundational presupposition that’s been disproved with hard evidence. Will individuals always act in their own self-interest, to the detriment of group outcomes? Despite the broad acceptance of philosophical and economic theories built on the answer being yes, the evidence says no.

As it turns out, it’s not that simple to assume an understanding of the complex motivations of other individuals. If you were to take that assumption, compound it from individuals to groups, and then build an economic theory on top of it, you’d have a difficult time defending the foundation of your economic model. Fortunately for your theory, most people won’t dig that deep, especially if your theory props up their existing worldview.

We can see that there’s enough question already about the foundational concepts of behavioural motivation that our primary economic theories are built upon. Even if those assumptions need overhauling to improve our economic models, we’ve been working with them for over two centuries already. When we turn to an examination of online community collaboration to product free and open source software, we’ll find that these assumptions and models are even less applicable, and they break apart almost instantly.

Notes

[footnotes_block]Works Cited & Further Reading

- Benkler, Yochai. “Coase’s Penguin, or Linux and the Nature of the Firm” (Yale Law Journal, 2002)

- Bollier, David. “The Only Woman to Win the Nobel Prize in Economics Also Debunked the Orthodoxy” Evonomics (28 July 2015); Excerpted from Bollier, David. Think Like A Commoner: A Short Introduction to the Life of the Commons (2014)

- Brown, Vivienne. Review of Capitalism as a Moral System: Adam Smith’s Critique of the Free Market Economy by Spencer J. Pack and Adam Smith and His Legacy for Modern Capitalism by Patricia H. Werhane in The Economic Journal Vol. 103, No. 416 (Jan., 1993), pp. 230-232. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/2234351. Accessed December 2024.

- Buchanan, James M and Tullock, Gordon. “Individual Rationality in Social Choice” (Chapter 4) in The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy (1958)

- Coase, R.H. “The Nature of the Firm” in Economica Volume 4, Issue 16 (1937)

- Geher, Glenn. “The Prisoner’s Dilemma in Everyday Life: How game theory can shed light on modern problems” Psychology Today, December 2021

- Heath, Joseph. “Methodological Individualism” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2024)

- Higgs, Henry. The Physiocrats: Six Lectures on the French Economistes of the 18th Century (1897)

- Himanen, Pekka. The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age (2001)

- Hofstadter, Richard. “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” Harper’s Magazine, November 1964

- Kahneman, Daniel. Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment (2021)

- __________________. Thinking, Fast and Slow (2013)

- Kendzior, Sarah. They Knew: How a Culture of Conspiracy Keeps America Compliant (2022)

- Lasch, Christopher, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (1979)

- Levy, Steven. Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution (1984)

- Pentland, Alex. “The Rational Individual” in Brockman, John, This Idea Must Die: Scientific Theories That Are Blocking Progress (Edge Question Series, 2015)

- Pinker, Steven. Rationality: What it is, Why it Seems Scarce, Why it Matters (2021)

- Raymond, Eric. The Cathedral and the Bazaar (1999)

- Scott, John. “Rational Choice Theory” in Understanding Contemporary Society: Theories of The Present, Browning, G., Halcli, A., and Webster, F., eds. (Sage Publications, 2000).

- Shirky, Clay. Here Comes Everybody (2008)

- Smith, Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776)

- __________. The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759)

- Tobin, James. “The Prisoner’s Dilemma“

- Weber, Max. The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1930 English translation; 1904-5 German)

- Zimbardo, Phillip. The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil (2007).

Notes

- David Bollier, “The Only Woman to Win the Nobel Prize in Economics Also Debunked the Orthodoxy” in Evonomics (28 July 2015).

- John Scott, “Rational Choice Theory“, 2000

- See Buchanan & Tullock, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy (1958)

- Scott, op. cit.

- Scott, op. cit.

- Alex “Sandy” Pentland, “The Rational Individual”

- ibid. This partially illustrates why entrapment is a legal defense, as people can be induced to do something that they wouldn’t, had they been left to make a determination without influence or inducement. On the other hand, passing blame for an action even by citing miliary orders has not been accepted as reason to excuse an immoral action, neither in the Nuremburg Trials nor in the acts of torture at Abu Graib prison. For a much longer discussion, see Philip Zimbardo, The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil (2007).

- Later, we’ll see how an incorrect assessment of these is compounded as they are misapplied to the economics of open source.

- Bollier, op. cit.

- We don’t need to tackle the whole theory of capitalism, but an understanding of the social science that the economic model rests upon will help in evaluating how the social science applies to FLOSS communities and the economics of open source.

- Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). Note the phrase “invisible hand”, which we’ll pick up later.

- See Henry Higgs, The Physiocrats: Six Lectures on the French Economistes of the 18th Century (1897)

- To some, Smith’s idea may seem almost as farcical as pulling oneself up “by his own bootstraps.” A full discussion is beyond our current mandate, but we might still drop a rhetorical question about what happens when the interests of the wealthy and the poor are not aligned. Had Smith been a pauper, would his economic theory have made the same assumption?

- Brown, The Economic Journal, Vol. 103, No. 416 (1993)

- Including roads and bridges for example, which as we’ve seen are a form of common pool resources (CPR), or commons, which is relevant to our overall theme.

- See Oliver Stone’s 1987 movie Wall Street

- The actual quote is “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed in all of its forms—greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge—has marked the upward surge of mankind and greed, you mark my words, will not only save Teldar Paper, but that other malfunctioning corporation called the USA.” As with many popular quotations from movie characters, it is commonly shortened to the pithier, more memorable version, even in the official 20th anniversary version, as shown.

- Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (1979)

- See Max Weber, The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-5 in German; English translation in 1930). Weber placed the roots of modern capitalism in the Protestant ethic.

- See for example, Eric Raymond, The Cathedral and the Bazaar, Pekka Himanen, The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age, and Steven Levy, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution

- R.H. Coase, “The Nature of the Firm” in Economica Volume 4, Issue 16 (1937). Coase offered an economic explanation for why individuals form partnerships, companies, and other business entities.

- See inter alia, Pinker’s Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters

- See for example, Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow and Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment

- See “Methodological Individualism” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- See “The Prisoner’s Dilemma” at University of Michigan Heritage Project.

- Trekkers and sci-fi nerds may hear a version of the phrase the voice of Mr. Spock.

- I might also make a cynical observation about how differently these moral and ethical questions are dealt with in the disciplines of law and psychology as compared with economics.

- The fact that some level of social engineering is necessary begs the question of how applicable Smith’s “trickle-down” notion is outside of economic theory (or inside, for that matter). An example might be the establishment of herd immunity through vaccines. At various times in the fight against certain diseases, children were required to be vaccinated in order to register for public school, thus incentivizing individual behaviour that protected the group.

- Arguments have similarly been made that the effort spent to enforce copyright against piracy in places such as in the music industry is so costly (yet ineffective) that if it were dropped completely, the retail price would be reduced enough that the incentive for piracy all but disappears. The assertion is that the cost to the consumer is reduced to the point that it is paid unbegrudgingly and without excluding access to the least fiscally-able. The only losers in the exchange are the for-profit piracy-fighters.

- When these presumptions become accusations, and the accusations are similar to what the politician may already be engaged in (whether or not the behaviour is preemptive in nature), we find what Sarah Kendzior refers to as “preemptive narrative inversion.” In those cases, the public is less believing that the accuser is guilty of the same behaviour, since they’re making the accusation — one which turns out to be false.

Pingback:Breaking the Status Quo is The Future of WordPress – YAWP.foo